// Interview: Etéreo Armando Medina

Director General of the Penitentiary System, Panama

JT: An incarceration rate of 395 people per 100,000, a high rate of pre-emptive arrests and overcrowding are some of the challenges facing the Panamanian penitentiary system (source: PrisonStudies.org). How do you manage these challenges and how do you think they will progress?

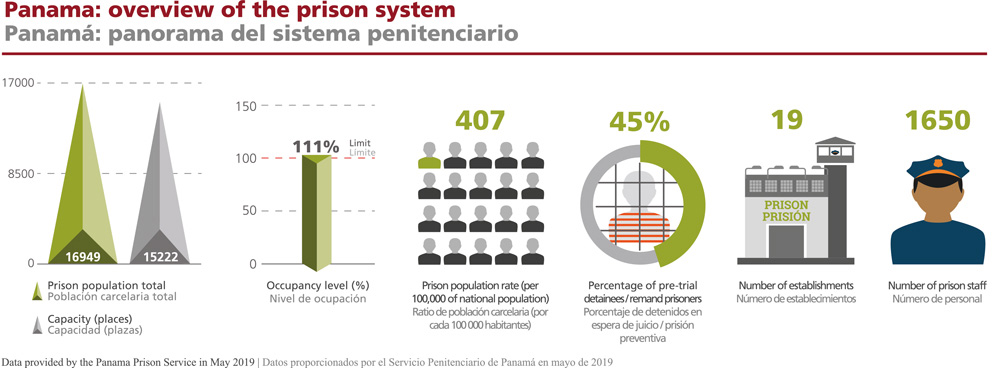

EAM: For 2016, the number of pre-emptive arrests was around 63%, which meant a very low percentage of convicts. With the entry into force of the Adversarial Legal System (SPA, by its Spanish acronym) in the provinces of Panama, Colón and Panama Oeste, this varies significantly, because in the provinces of the countryside, where the SPA already existed, we had more convicts. Today, the rate of people in trial is about 45%.

In the penitentiary system, there is an overpopulation of about 1,700 people. The established capacity is 15,222 places and there are 16,949 people incarcerated. We have held inter-agency meetings, in harmonious collaboration with other State entities, to see how we can reduce the overcrowding and incarceration rates. Before the SPA came into force —even before I was the general director of the penitentiary system, as an adviser to the Minister’s Office—, we carried out a data cleansing session, to try to locate people who had been in trial for a long amount of time, and see how they could get a sentence, or speed up their paperwork and see how to end the process.

The homicide rate in Panama has declined by 23% in recent times. However, crimes against economic assets, such as theft and robbery, are committed daily and they increase the prison population. It is an oscillating number (the highest during our administration has been 17,500), but we have kept it fairly stable with the granting of extraordinary measures, such as parole and penalty-lowering, and also working hand-in-hand with the judicial branch and the Public Prosecutor’s Office in order to grant them probation or some other type of alternative or measure or criminal justice substitute.

In terms of infrastructure, we are building a new rehabilitation centre with capacity to hold 700 incarcerated women, for an amount of 27 million dollars. It’s going to be a modern centre, with a university, a school and a daycare inside. The penitentiary centre that will be developed in Colón will have a capacity of 1,350 incarcerated people, and the construction programme is being managed by the UNOPS. This is an investment of 88 million dollars, so we are investing to improve the conditions of habitability.

We are also completing the construction of a modern pavilion at the La Joya Penitentiary Centre, which will serve as a model for renovating the rest of the centre. In addition, we have already approved the construction, the environmental impact assessment and the plans of a new pavilion in La Joyita.

We have also remodelled some facilities of the El Renacer Penitentiary Centre and delivered the feasibility study for the construction of the new penitentiary centre of the provinces of Coclé and Veraguas. In addition, we have requested the contracting of the new penitentiary centre’s feasibility study of Panama Oeste, and we are in the process of identifying a prospect for the new penitentiary centre of the provinces of Herrera and Los Santos.

The penitentiary system plays a predominant role with unconvicted persons in its custody. With the penal reform of 2017, they can take advantage of study and work programmes in prison.

JT: What is Panama’s progress status in the subject of sentences and alternative measures, that is, non-custodial sentences?

EAM: We have a system that is divided into two lines: one in which incarcerated people can access sentence replacements and penal substitute measures, the requirements of which are in the legislation; and another line in which they benefit those whose sentences are under 60 months, where the judge replaces the sentence either with community service or with payment of a financial penalty.

Many times, people make use of the opportunity, give their service to the citizenry and become productive for the State. Other times, they do not take advantage of it, do not comply with the alternative penalty, and then enter the penitentiary system. This reality indicates that, although it is true, for the Panamanian penitentiary system, the existence of substitute penalties or criminal justice substitute measures is very good, it is no less true that the lack of certain controls, which need to be established, leads to people maybe not being able to use the benefits they are granted.

The penitentiary system plays a predominant role with unconvicted persons in its custody. With the penal reform of 2017, they can take advantage of the study and work programmes that exist in prisons—so that, in the event they are sentences, they have already been able to somewhat reduce their sentence in advance. This will allow them to serve two-thirds of their sentence more promptly and benefit from one or another criminal justice substitute measure.

On the other hand, the use of electronic monitoring bracelets is contemplated in our legal system and, at this time, the Ministry of Public Security, as part of the executive branch, is analysing a pilot plan in coordination with the judicial branch, the Public Prosecutor’s Office, the National Police and the penitentiary system. The role of the Ministry of Government is to work as a team with the aim of making electronic bracelets become a real possibility and be implemented.

Electronic bracelets benefit both the community and those who are, for example, first-time offenders, so that they do not go to a prison with people who make crime their way of life. It also translates to savings for the State, because if we consider how much it costs to keep a prisoner in prison, the use of a bracelet is much more feasible and economical.

JT: What is your assessment of the impact of the UNODC-ROPAN prison reform projects funded by the United States and the European Union between 2010 and 2017?

EAM: All that is left is to thank these United Nations agencies for their continued and selfless support of our penitentiary reform. UNODC-ROPAN were strategic partners that supported us greatly with funds from the U.S. Embassy in Panama – and that was carried out from 2010 to 2014 – with the objective of designing and implementing a prison policy that could bring the system to meet international standards. A very important point was the reopening of the Penitentiary Training Academy, which would allow us to train our staff.

Another very important component was within the Cooperation and Security with Panama project (SECOPA, by its Spanish acronym) in which, between 2014 and 2017, the goal was security and rehabilitation, with the objective of improving the living conditions of inmates. IntegrArte, which is our first penitentiary brand, was born within this project.

In addition, these partners supported the development of the penitentiary career for custodial and technical staff, which was a debt of the Panamanian State, since 2005. Not only did we manage to adopt the resolution, but it became the law of the Republic. Today, we have an established penitentiary career path, a system that benefits staff, which has had a positive impact on the development of our social and labour reintegration programmes.

A third aspect was the consolidation of progress in prison reform. Our administration focused on this reform plan; we updated it, modernised it and, through UNODC-ROPAN, we were able to work on international standards to improve prison infrastructure conditions. All this goes hand in hand with a profound penitentiary reform in the matter of professionalising our staff, supporting incarcerated people in social and labour reintegration projects, and guaranteeing respect for human rights.

At the moment, the penitentiary reform is being carried out with diverse international support. For example, the International Committee of the Red Cross supports us in improving infrastructure; the European Union’s PACCTO programme provides training support on anti-corruption, organised crime and security issues; and the U.S. Embassy continues to support us specifically on prison security issues, which has allowed us to strengthen the corps of custodial staff and create specialised units.

We still do not have the necessary number of prison officers to have absolute control of the prisons, so we rely on members of the National Police.

JT: In a report (Source), the United Nations Subcommittee against Torture has pointed to human rights abuse, unhealthy conditions of incarceration, corruption among staff and problems related to gang self-governance. What measures have been taken to improve these conditions and, above all, to combat corruption and organised crime?

EAM: The Subcommittee came at the invitation of the Panamanian State itself and, faced with that report, we took concrete measures. Regarding health-related matters, we held inter-institutional working groups with the Ministry of Health, where we were able to deal specifically with the healthcare issue, which, by government agreement, is provided by the Ministry of Health. We are working day by day on training staff, equipping some clinics and appointing more doctors. Trying to always improve the area of healthcare is hard work and a challenge.

On the issue of security and self-government, we work hand in hand with the National Police and other security agencies. We still do not have the necessary number of prison officers to have absolute control of the prisons, so we rely on members of the National Police. We work hand in hand with the police on inspections, we increased the levels of technological security to prevent the entry of unauthorised objects, and we strengthened the Inspector General’s Office department that investigates acts of corruption. We have presented the authorities with 39 criminal complaints regarding corruption cases, we have approximately 80 internal investigations in process, and more than 50 people related to this type of event have been dismissed. Corruption in prisons does not end, but we must face it and not tire of fighting it.

As for gangs – just like in society, they exist within penal centres, but with these routine security procedures, it has been possible to maintain activities and good coexistence.

JT: What is the state of technological development and computerisation of Panama’s penitentiary system?

EAM: Along with the support of UNODC-ROPAN, we went and got to know the penitentiary information system of El Salvador, obtaining the know-how of this subject—and we did it in a Panamanian way. At the moment, our Penitentiary Information System (SIP, by its Spanish acronym) is very flexible, with 62% programming progress and two almost complete modules (the judicial and security modules). The treatment module has progressed 12% and the visit module has not yet started. This has allowed us to have reliable information regarding the inmates and to update their information in the database. We want the system to be based on a flow, in processes, and we will probably have help from international institutions to be able to bring our database to 100%.

The subject of penitentiary information has been an achievement of this administration: we have a proprietary and armoured database. In addition to this, with the SECOPA project and the Inter-American Development Bank, we have made the first penitentiary census. We finished it in September 2018, and we are hoping that the Institute of Statistics and Census of the Comptroller General of the Republic gives us the information that will allow us to develop better public policies regarding security.

programme in prison

JT: We know that two prison work projects are underway: IntegrArte (which is the first penitentiary brand in Panama) and EcoSólidos. What are these projects and how important are they for the inmates, the penitentiary system and the community?

EAM: EcoSólidos is a project that was born in 2014, in the La Joyita Penitentiary Centre, promoted by the inmates. They started recycling the rubbish that, at that time, smothered them. La Joyita is the centre with the largest prison population in the country and produces approximately 50 tons of garbage. With this project, it has been reduced by about 80%.

EcoSólidos reduces, recycles, reuses and resocialises. And now we have formally legalised it, allowing participants to learn to recycle and reduce their sentence—for every two days of work, their sentence can be reduced by a day. In addition, we already have ex-inmates who have worked in this programme and now have recycling companies or work in the Ministry of Environment. This proves that it is a programme that really supports reintegration into society.

The subprogramme “Sembrando Paz, Reforestando Vidas” [Sowing Peace, Reforesting Lives] is a garden centre that developed with EcoSólidos. Last year, inmates planted a total of 5,000 saplings, and this year, for the big day of reforestation, we are ready to plant 20,000 saplings that have been cared for and cultivated in a penitentiary centre that used to be one of the most dangerous and is now a model for others prisons. A third by-product of EcoSólidos is the environmental barriers that are being used to catch rubbish in the country’s rivers.

EcoSólidos began with 200 inmates and currently involves more than six hundred in La Joyita Centre, and already extended to other centres.

IntegrArte was born in 2016, as part of the support from UNODC-ROPAN and the European Union. Its objective is to train the incarcerated population and give them tools so that, once released, they can be useful to society. This penitentiary brand has been launched and participated in fairs and bazaars, exposing the items (works in wood, clothes, fabric, etc.) that are created in the prison. In addition, we let society acknowledge the talents of the incarcerated population. We have three display kiosks of IntegrArte products in Panama City.

At this moment, IntegrArte operates in four penitentiaries and its objective is the nationwide expansion of the programme. Its impact is substantial: it has generated interest from artists, private companies and foundations. In addition, inmates who work in IntegrArte have access to entrepreneurship courses.

It has been hailed as a model programme within the objectives of sustainable development and it integrates gender equality, which has allowed us to participate in exhibitions in Europe and in penitentiary brand congresses.

//

Etéreo Armando Medina holds a degree in law and political science from the University of Panama and a master’s in criminal procedural law, criminal law, alternative methods of conflict resolution with emphasis on arbitration and higher education. He has a certificate of advanced study in the topics of adversarial criminal justice system and management and administration of human resources. He is the General Director of the Penitentiary System of Panama since January 2017. Between 2009 and 2014, he held judicial positions such as mediator and judge of guarantees of the adversarial criminal justice system.