// Interview: Valdeci Ferreira

Executive Director of the Brazilian Fraternity of Assistance to the Convicted, an entity that groups the APAC recovery centres in Brazil

JT: What is the APAC method?

VF: APAC is a non-profit civil law association, which stands for Association for the Protection and Assistance of the Convicted. APAC was born in 1972 in the city of São José dos Campos, São Paulo, and was conceived by the lawyer and journalist Mr. Mario Ottoboni.

APAC was born to recover the inmate, protect society, assist victims and promote restorative justice. To achieve these objectives, we apply our own criminal therapy, which we call the APAC method.

The method is a set of 12 key elements: community participation (1); the person who is receiving help or the “recuperando” (2) (remembering that within the APAC we refer to those convicted in the justice system as “recuperando“); work (3); spirituality (4); legal assistance (5); health care (6); volunteer work (7); merit (8); human appreciation (9); the family of the “recuperando” and the family of the victim (10); the liberation days with Christ (11); and the social rehabilitation centre (12), which is the space where we apply the method.

The great result of the application of these elements is the changed mentality of the “recuperando“. In APAC, it is not enough to change one’s behaviour. By this I mean that the recuperando must realise the bad things they have done, take responsibility, and from then on, change their behaviour, their lifestyle and plan a new future.

The APAC methodology is supported by a tripod of love, trust and discipline. We believe that only love can heal the person and the wounds of rejection. And love manifests itself through volunteers, work teams and is constant, free and unconditional. It is also a method based on trust, to the extent that all the keys to social reintegration centres, which are still prisons, are in the hands of our “recuperando“. The discipline in APAC is extremely strict. There is a routine that begins at 6am and goes on until 10pm, where work and education are mandatory, including cleaning the facilities and participating in acts and lectures of human appreciation and in cell meetings.

In APAC, it is not enough to change one's behaviour. By this I mean that the recuperando has to realise the bad things they have done, take responsibility, and from then on, change their behaviour, their lifestyle and plan a new future.

JT: How and why does this alternative method arise in the sector of execution of criminal penalties in Brazil?

VF: The initial context is the same as today, but now there are more aggravating factors. When Mr. Mario visited the “Humaitá” prison he found a warehouse of men, mostly young, abandoned and without hope. Unfortunately, although the penalty has this dual purpose — to punish and to recover — in our prisons only one mission is fulfilled, which is that of punishment. The state arrests people and returns them to society in an even worse condition. The context at that time was serious, but now it is even more so. Today Brazil has around 820,000 prisoners living in subhuman conditions. Prison has become a major industry and the one that grows the most in Brazil (between 8 and 10% per year). In Brazil, people are arrested often, in many cases in bad conditions, and prison does not offer life-changing conditions. There is no treatment for the prisoner; no doctor, no psychologist, no work, no school, and no human appreciation. Precariousness exists in all prisons, and now there is an aggravating factor: the existence of criminal factions who, from inside the prisons, command drug trafficking, murders and extortion.

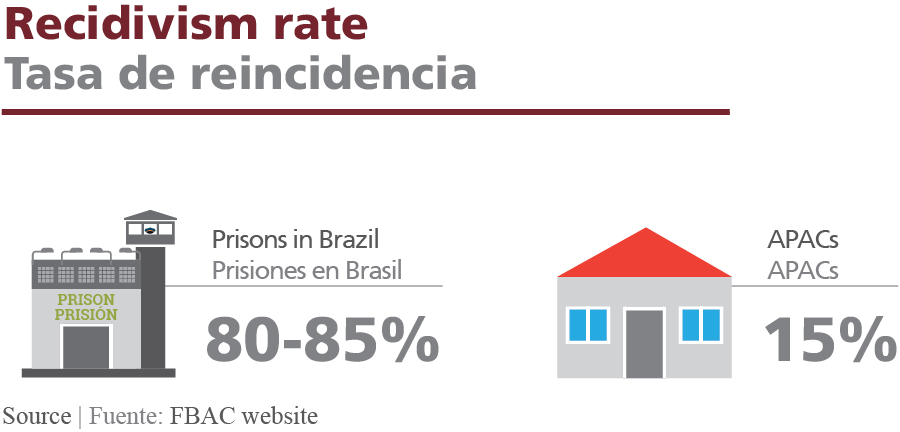

However, APACs are not the model to be followed. Although the percentage of recidivism is low (15%), we cannot present APACs as a ready and finished model. We are talking about 46 years of studies and development. We are not a franchise model and we don’t want to replace the prison system. APAC is not a people recovery factory. You do not put an individual in one side and see them come out as a recovered person on the other side. APAC emerged in 1972 and continues to be an alternative that we believe to be viable, either because it reduces the rates of recidivism, which today in Brazil are between 80 and 85%, or because the rates of escape are very low and we have never registered rebellions.

In APACs, people are worth what they are and not what they have. And we have also managed to reduce the cost; an inmate in APAC has a cost of 1/3 compared to the inmate in the common system. There are several advantages, whether executive, legislative, or judicial, that the authorities in Brazil are becoming aware of regarding the APAC methodology and are disseminating these advantages in several states.

I visited a prison in Itaúna 36 years ago and I was deeply moved by the conditions of abandonment and misery of that prison unit, and since then I have done nothing else in my life but take care of the recovery of inmates. I have been travelling through Brazil from top to bottom and, increasingly, I see the importance of spreading the APAC method.

APAC humanises prisons and punishment; we are synonymous with hope. It’s a light at the end of the tunnel, both for inmates and their relatives. It is also a light at the end of the tunnel for those authorities who are not only concerned with convicting, but also with preventing crime and recovering people who are abandoned in prisons.

JT: What are the main differences between APAC centres and public institutions for the enforcement of custodial sentences?

VF: I would say the main difference is that APAC complies with the law. In Brazil we have a law of penal execution – law 7210 of 1984, which unfortunately, in the common prison system, is a dead letter. In the APACs we comply with the law of criminal execution, in areas that concern rights, but also in those that concern duties. Treat the human being as a subject of rights and duties, with respect so that he can respect himself also. And with love so he can then respond with love. Nobody is unrecoverable. We start from that premise and that is our motto.

We are saddened that APACs have become known for complying with the law, when in fact this exception should be the rule throughout Brazil.

In Brazil, people are arrested often, in many cases in bad conditions, and prison does not offer life changing conditions. There is no treatment for the prisoner; no doctor, no psychologist, no work, no school, and no human appreciation.

JT: What criteria must inmates meet in order to be transferred to an APAC centre and what is the selection process like?

VF: There are four objective criteria that are defined in an ordinance of the Court of Justice of the State of Minas Gerais and that have been copied by courts in other states, where they are also being applied. The first criterion is that the detainee must have his legal situation defined, that is, we only work with those who have been convicted by the court of justice and we do not work with provisional prisoners. The second criterion is that the family should stay at home in that city where APAC is located, because we work with the inmate and their family at the same time and, therefore, it is important that their care circle be as close as possible. The third criterion is that they express in writing their desire to be transferred to an APAC to change their lives and that they are willing to comply with the discipline and regulations. Finally, the criterion of seniority by date of sentence.

In the cities where we have APAC, there is a waiting queue and, when vacancies arise, they are transferred, regardless of the crime committed and the time of conviction. In APACs, we have people convicted of drug trafficking, murder, paedophilia, rape, assault; people sentenced to 5, 10, 15, 30, or even 80 years. So much so that in APAC there is a phrase written in huge letters: “HERE COMES THE MAN. The offence is out there!”.

We work with the human being.

JT: Is there repentance and non-compliance among the detainees in APAC?

VF: Yes, in a small number, but it happens because of the fact that although many people seem to want to comply with the rules, in reality they want to escape. This may also be because they heard the food is good and that there are doctors and psychologists. But knowing this, in APAC we have established the first three months as the adaptation period. The first month is the diagnosis period, the second month is the detox period, and the third month is the motivation period. Obviously, in these first three months we give special attention to those who have arrived, not least because in APAC we are working with the most problematic people in society. Those who serve time in APAC have failed the family institution, school and church. They have failed society as a whole. We need to take a special approach.

The quitters go back to the common system, but they can get in line again. Today’s unrecoverable person may be tomorrow’s recoverable person. It is often from the system that they are able to see the sky. You have to go back to the system to remember that in APAC you would have a chance.

As a person, as an idealist, and as a Christian, the world I envision is a world without prisons. It's a utopia. For as long as this utopia does not come about, let us at least make prisons more humane and let people be treated with respect and dignity. I think we're on the right track.

JT: What is the geographic scope of the APAC method in Brazilian territory and how does it impact the country’s prison system?

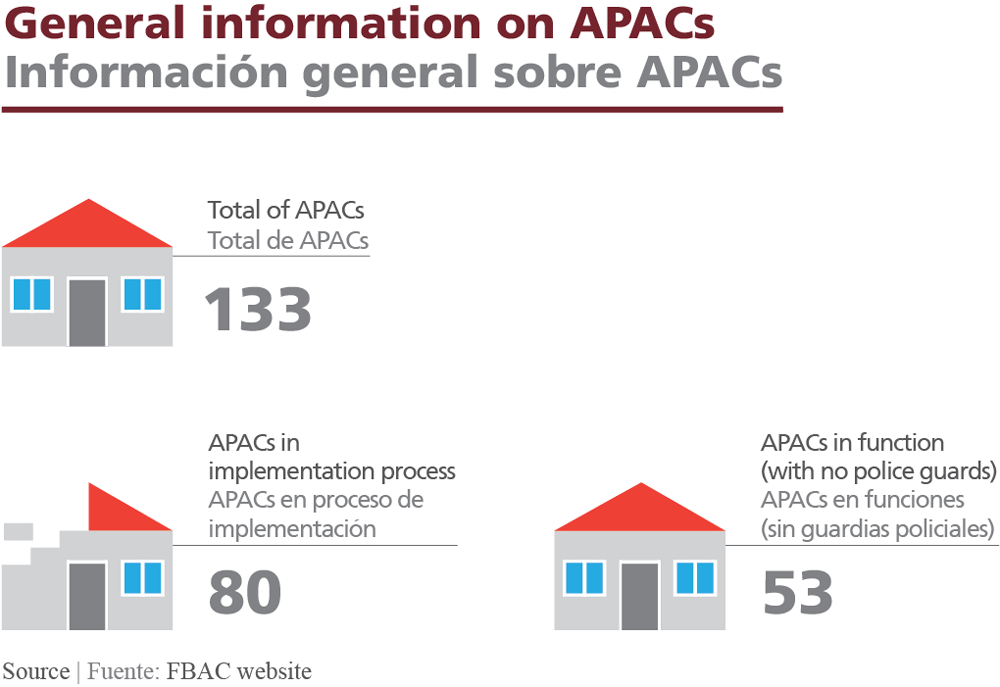

VF: Today we have 54 APAC centres in seven federal states. We have dozens of others, around 90, in different stages of deployment. As our social reintegration centres are inaugurated, judges are transferring prisoners and they are integrating themselves into this network.

The FBAC monitors, from the first step: first the public hearing, then the seminars and training of volunteers, and even the verification of land and architectural plans. After the inauguration comes the process of recovery, from the moment the person arrives at APAC until they gain freedom. Despite the rapid growth we have seen, we currently have 4000 “recuperando“. It is still a very small volume in the Brazilian context, but we are an island of hope in the sea of suffering that is the common prison system. Even if we closed down all APACs today, we would have accomplished our mission. We are doing what nobody has ever dared to do in the history of mankind: handing over the prison key so that the prisoner can take care of it and not run away. APAC is the great revolution of the prison system. Prisons without guards, without police, without weapons, without violence, without corruption, without drugs, without discrimination, where people work and study so that the criminal can become a good citizen and a useful person to society.

However, we are swimming against the current, because the prison system is a big industry. We have not grown as much as we could because many don’t know the APACs and many who know don’t want them because they don’t want to lose the privileges they’ve always had. Sometimes it is important to maintain the status quo in prisons in order to perpetuate social discrimination. This is what happens in Brazil and in so many other countries in the world.

Fortunately, we are already partially applying the APAC method in several countries, including Chile, Costa Rica, Uruguay, the Netherlands, South Korea, USA, Italy, Hungary, Norway and Germany. And there are movements in other countries, such as Portugal and Paraguay, where there is already a legal part.

JT: What is the financing model of the APAC method in Brazil? Do you have international support?

VF: We assume that it is the constitutional duty of the State to build, equip and maintain prisons. APACs run social reintegration centres which, although they do not look like prisons, are prisons. The great financier is the State. Each APAC is legally and financially autonomous and enters into a partnership with the State Government; thus, the State transfers resources to APAC monthly (per capita value of the number of “recuperando” there), and APAC, in turn, hires people to work in the administrative sector, pharmaceuticals, food, transportation, school supplies, and, at the end of the month, renders reports. The fact that the State is willing to fund us is a sine qua non for our method.

In Brazil, the average per capita of maintenance of an inmate is 3000/3500 R$ per month. In APAC it is 1000 R$ per month. The big difference is due to the co-management model in which the “recuperando” and volunteers participate.

The training is permanent, and we carry out this work with the Court of Justice, the State Government and the Court of Audit of the State. We involve all partners because APAC in Minas Gerais and Maranhão, where the project is most advanced, is a public policy of the Court of Justice and the State Government. This training is the work of many hands.

APACs are legally and financially independent. They can receive donations. There are professional workshops, a bakery, a carpentry shop and a vegetable garden. APACs can also seek other resources besides state partnerships.

JT: What are the expectations for the future regarding APACs?

VF: As a person, as an idealist, and as a Christian, the world I envision is a world without prisons. It is a utopia. For as long as this utopia does not come about, let us at least make prisons more humane and let people be treated with respect and dignity. I think we are on the right track. FBAC’s goal is bold: we want to implement an APAC in each region in Brazil, which is more than 2000. I hope that the Federal Government will adhere to this APAC proposal and release resources for granting new social reintegration centres, so that we can expand our method in Brazil.

//

When he was 21 years old, Valdeci Ferreira decided that his life’s purpose was the rehabilitation of criminals. His dedication over the last three decades made the number of APACs leap from 1 to 49 units spread out in five Brazilian states, accommodating approximately 3,500 convicts. He was received in 2016 by Pope Francis as part of a conference organised by UNIAPAC (the Christian Union of Business executives) on Business Leaders as Agents of Economic and Social Inclusion. He has won several awards including social entrepreneur of the year in 2017. He is the Executive Director of FBAC.