// Interview: Francesco Basentini

Director General of the Penitentiary Department, Italy

JT: Five years ago, Italy began to tread the path of a penitentiary reform when the then President of the Republic sent a message to the Chambers that the prison issue was to be considered a “hot topic to be tackled in a short time”. The European Court of Human Rights had condemned Italy for the “chronic malfunctioning of its penitentiary system” on a sentence dated from 8th January 2013 – the Torreggiani ruling. In 2018, the prison reform was cancelled following the change of Government with only the Juvenile Justice reform having come into force.

Is prison reform something that is on the new Government’s horizon?

FB: There are no reform plans to date. We certainly need to change, but reforms should leave a mark, rather than be a tangle of confused ideas. Above all, we need to improve the correctional system outcomes, rather than talk about reforms in general.

I have been travelling for months around our prisons, with targeted meetings with all the superintendents, commanders of the Prison Police, educators, work cooperatives and institute directors, with the aim of identifying efficiency needs at the administrative level.

My goal is to increase the results that do not require legislative interventions or, at any rate, minimum levels of political decisions. This is something completely new that has not been done before.

JT: The latest SPACE I data showed that Italy is over the European Union’s average as regards the suicide rate per 10,000 inmates – the EU rate is 5.5 whereas Italy’s is 7.4.

How would you comment on this troubling figure?

FB: I would partially agree with the figures, even if there are European countries where the peaks are much higher. Even the northern European countries, which offer an extraordinary quality of life and indicators of civilisation, are not always models to be followed when it comes to the number of suicides in prison. There is a serious problem in Italy that is linked, above all, to the path not only of life but also to the health of many of the prisoners. The Prison Administration does not deal with health care, especially psychiatric health care. There are so many problems with adaptation and so much existential distress in prisons, but unfortunately, those issues are monitored by the regional body that has competence in the field of health and is something on which we obviously cannot intervene as much as we would like.

JT: Could you please tell us about the state of play of dynamic surveillance in Italian prisons?

FB: A dynamic surveillance scheme is being implemented in each Penitentiary Institute, according to the methods that the prison governor has decided to use, hence creating a series of many self-managed systems. Let’s say that there was a desire to resort to solutions that were probably slightly unsophisticated in order to create respect for the Torreggiani ruling [1].

The total number of square metres available in prisons divided by the number of prisoners gives a numerical ratio that is perfectly in line with what has been imposed by the Torreggiani ruling. Dynamic Surveillance does not only mean space areas and numbers, but also many other things, such as our commitment to prisoners as regards how we occupy their time, and the way in which we help them to give meaning to life, even though they are in detention. So, the Torreggiani ruling is just a small piece of the whole system; that’s why I plan to make a handbook to stabilise the idea of dynamic surveillance.

Dynamic surveillance is defined as an ‘open regime’, where the confinement in closed cells is limited to the nights only. During the day, from 8 a.m., all cells of all inmates in low and medium security are open and prisoners are free to move and interact in their wings, where only CCTV cameras control their activities. The prison police remain outside of the wing gates. They enter the wings only to accompany inmates to their different activities or for very specific duties. This management model was supposed to integrate a reinforced plan of rehabilitation activities, to grant the inmates more social and reintegration activities.

There are no reform plans to date. We certainly need to change, but reforms should leave a mark, rather than be a tangle of confused ideas.

JT: Although the prison population had been significantly reduced in the period following the Torreggiani case, it has increased in the course of 2016 and, according to the Committee for the Prevention of Torture (CPT) report (2017)23, overcrowding persists.

To what extent does the rise in the prison population jeopardise the progress that had already been made?

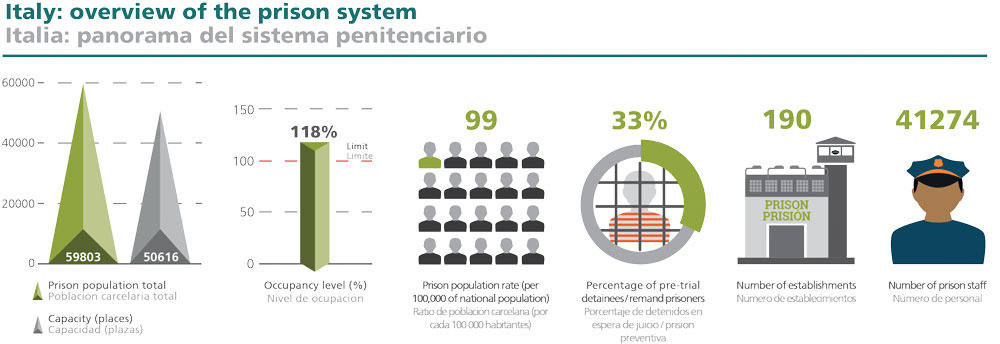

FB: Our data differ from the CPT’s. Our medium-term calculations indicate that between 2011 and 2018, prison population evolved from 66,897 (with a capacity of 45,700 places) to 59,275 (with a capacity of 50,622 places). So, the number of prisoners decreased and capacity increased. Moreover, we have new infrastructure still being built.

JT: What technological developments are taking place in the Italian prison system?

FB: Technology is an excellent ally of the prison world, but also one of its worst enemies. For example, the use of drones for criminal activities such as the delivery of illicit goods inside prison facilities. Technology can help us intercept those drones, however, it is particularly expensive. We have 190 prisons using jamming technologies to combat drones.

As regards further technological implementations, in Northern Italy, in particular in the prisons of Triveneto, a new model of a “technological prison” is being tested. It is among the most advanced in the world and is the result of public-private collaboration.

Moreover, the new Experimental Laboratory of Padua (the ELPeF), has started very advanced experiments (see the case here). As the studies and trials are not yet completed, I can’t provide details, given the legal and political implications, as well as the security aspects.

With the new Security Decree that has just been approved by the Parliament, all this technological framework of prison transformation has already begun to take shape.

From the developments in Padua, I can assure that the Italian penitentiary institutions, at least the most advanced ones, have technological processes in place that will change the face of the penitentiary system in the coming years. European funds are our challenge for this new horizon.

[Between 2011 and 2018] (…) the number of prisoners decreased and capacity increased. Moreover, we have new infrastructure still being built.

JT: The author of the terrorist-hit in Berlin, in December 2016, has allegedly followed a violent radical ideology while incarcerated in Italian prisons (Source: The Washington Post, Suspect in Berlin market attack was radicalised in an Italian jail, December 22, 2016).

What kind of strategy and actions are being implemented to deal with violent radicalisation in Italian prisons?

FB: The Prison Police and many others are responsible for the observation and monitoring of prisons, which results in a flood of information of all kinds. When it is information that is not of the first stage or does not automatically have criminal relevance but concerns subjects at risk of radicalisation or extremist Islamic proselytism, it is immediately made known to the Judicial Authority, to other competent bodies and to all other police organisms.

Italy’s success in preventing radicalisation in prisons is precisely the sharing of information. The competence of the judicial bodies in charge and the administrative competence of the prefectural authority rather than of the governmental authority in matters of expulsions go hand in hand, instead of conflicting.

The information collected in the preventive activity of the prosecutors and district attorneys gives rise to a criminal investigation or proceeding if there is a hypothesis of crime; it can give rise to administrative measures, when there was no materialisation of the hypothesis of a crime but the intelligence suggests that the subject is carrying out activities of possible proselytism or, in any case, is a subject at risk of radicalisation. In the latter case, the information is passed to the administrative or governmental authority for expulsion orders.

JT: To what extent does the current counter-terrorism legislation support the prison system?

FB: The problem of violent radicalisation is even further upstream: certain regulatory structures and institutes have been appropriately created in “a climate of total emergency”. When laws are made in the field of emergency, there is an inevitable risk of adopting particularly broad wording or grammatical structures, such as the current legislation. The approach of each European country is to remove the at-risk citizen from their territory, but not to protect the European community as a whole.

JT: People who are under the radar of radicalisation observation are not transferred to their countries of residence or to those in Europe, and in particular the information is not transcribed in the transfer certificates required by European Framework Decisions. Is this a good policy?

FB: I consider it a totally incorrect practice. The approach adopted by all Community bodies, in general, and also those of individual countries in terms of investigation and combatting radicalisation, is totally unproductive. There is no model of information circulation, nor of information sharing and, above all, there is no model of reasoning, reflection and evaluation and, last but not least, there is no final decision model which should be common. In practice, it simply becomes the logic of moving the risk of a radicalised attack away from one’s own border. Europe is not united in terms of radicalisation.

JT: Italy is one of the very few European countries to have a Prison Police with the functions of a police force. Is this an advantage or should it follow the example of other countries?

FB: The role of the Prison Police (PolPen) is strategic because there is criminal activity in prisons, especially with regard to drugs, international trafficking, economic crimes, etc. In fact, the dynamics of organised crime in prisons is much more alive than we believe. We should really set up a serious investigative observatory in prisons, which should be the exclusive responsibility of the PolPen.

The PolPen is a treatment authority that observes, guards and supervises. I believe that its experience and professionalism should be properly valued in Europe. Proposals have been formalised to create sections of the Judicial Police at the Public Prosecutor’s Office. We require the opportunity to deal with the investigation activities concerning crimes that take place within prisons.

Placing the PolPen under the control of another police force must be categorically ruled out. Maybe to unite all the police forces would be an act of maturity that is impossible in Italy. We are now also the only country to have four police forces. The Italian model, of highly specialised police forces with differentiated skills, is the trump card in the challenge against terrorism and organised crime.

The PolPen is one of our strengths and it is a model to be exported to Europe. It is no coincidence that, from 2019, a group of 20 selected investigators will work alongside the national anti-mafia and anti-terrorism Prosecutor’s Office in the most heated investigations, integrating the actions of the Carabinieri, the State Police and the Guardia di Finanza (Finance Police). This has never happened before.

[1] Torreggiani and Others v Italy 43517/09 (ECHR, 08 January 2013): the European Court of Human Rights condemned Italy for violating article 3 of the European Convention on Human Rights due to prison conditions experienced by seven detainees in prisons, namely, prisoners were made to share cells measuring nine square metres with two other inmates, leaving them with three square metres of living space each. The ECHR obliged the State to implement the measures required to safeguard the rights of the applicants and other people in the same situation.

//

Francesco Basentini, who is graduated in Law, has been assigned the head of the Italian Penitentiary Department in June 2018. Before he has been Deputy Prosecutor at the court of Potenza, with anti-mafia and counterterrorism duties – he has been involved in famous cases of corruption in the oil sector. His post benefits from the same indemnity provided for the Chief of Police, the General Commander of the Guardia di Finanza and the Commander General of the Carabinieri and it entitles him to a seat on the National Committee for Order and Security.