// Interview: Gemma Tuccillo

Head of the Department of Juvenile and Community Justice, Ministry of Justice, Italy

JT: In 2015, the Directorate General for the Execution of Sentences in the Community and Probation was disintegrated from the Department of Penitentiary Administration to be coupled to the Juvenile Justice Department.

What was the rationale underlying this kind of organisation and what challenges and opportunities does it offer?

GT: In fact, this recent reform is in line with the new political strategy on security issues which – from a previous perspective aimed at the mere strengthening of the repressive sanctioning instruments – is now adapting to the guidelines drawn up by the Council of Europe Recommendations on community sanctions and measures.

From this new standpoint, a different and more complex approach to the treatment of adults under probation turns out. Despite the peculiarity of the treatment of minors under probation compared to adults, there is a common rationale underpinning the minors and adults’ world: the emphasis on the resocialisation and the reintegration of the offender in the community.

Hence, the Department’s objectives include: working towards the increase of community sanctions and measures; ensuring that the long and effective experience of the juvenile sector in the execution of community sanctions and measures may “affect” the adult sector; and adapt the Italian system to the Council of Europe’s guidelines, in particular to the Recommendation CM/Rec (2010)1 of the Committee of Ministers to Member States on the Council of Europe Probation Rules.

There has been a switch from a subordination function with respect to the prison sector to a sharing of the juvenile sector mission (…)

JT: What is the scope of the Department’s activity?

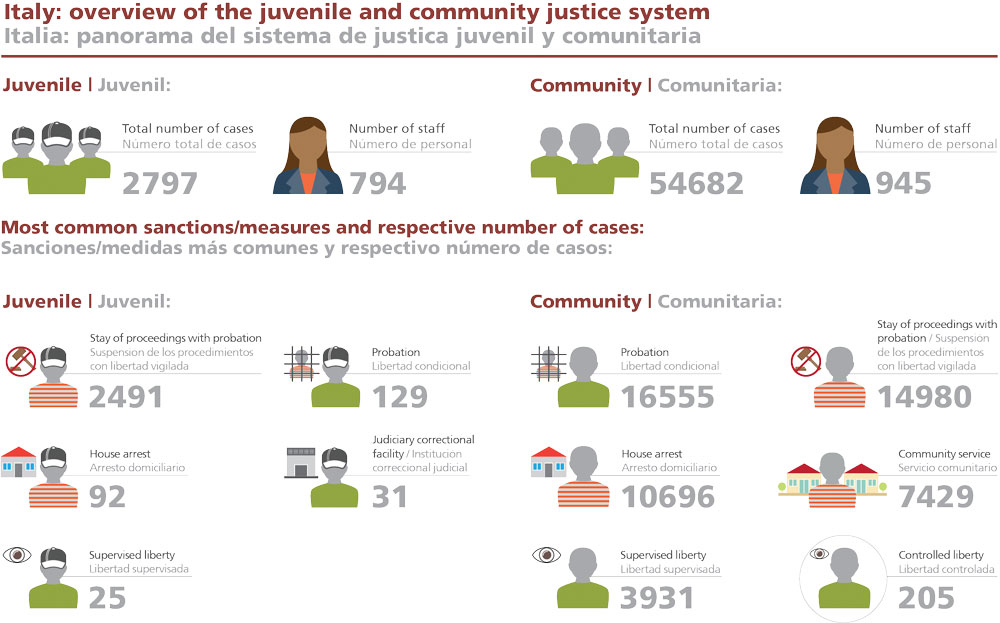

GT: To date, the local branches of the Directorate General for the Execution of Community Sanctions and Measures are: 11 interdistrict offices, 17 district offices, 43 local offices and 12 detached sections.

There has been a switch from a subordination function with respect to the prison sector to a sharing of the juvenile sector mission: developing community measures and sanctions so as to make imprisonment residual for the most serious offences only.

Thanks to the introduction of the “stay of proceedings with probation” for adults (already existent for about 30 years in the juvenile context), the execution of community sanctions and measures is becoming the main response to crime. Currently, out of 60,002 inmates, the people under community sanctions and measures amount to 54,682.

People accused of offences whose punishment provided for by the law does not exceed four years may ask, even before the trial, that the sentence be commuted to community service, together with voluntary activities.

Community sentences are more “just” and “safe”, thus more consistent with the sanctioning objective, which is to prevent recidivism. In addition, the use of community measures and sanctions makes it possible to respond to offenses even if they are minor. Alternative measures to detention (semi-liberty, assignment to the probation service, home detention) may be imposed in place of the prison sentence or after having served a part of it in prison.

Serving a sentence out of prison, which is not meant as a reward but is a penalty in itself, can be carried out within the community, with the support of other public and private agencies.

The approval of the new juvenile penitentiary law introduced new community measures for minors.

JT: We have read that both Juvenile and Community Justice, in Italy, follow the principle of minimum intervention (Sources: Confederation of European Probation, “Probation in Europe – Italy”, March 2016 and Scalia Vincenzo. (2005). A lesson in tolerance? Juvenile Justice in Italy. Youth Justice. 5. (33-43).

Could you please explain what said principle consists of and the practical outcomes it renders?

GT: The Italian legal system, through the Juvenile criminal proceedings (Presidential Decree 448/88) that entered into force in 1989, aims at the rehabilitation of the minors who come into contact with the justice system.

The juvenile criminal proceedings give priority to the educational function, reducing the afflictive nature of penal measures to the minimum and recognising the minor as an individual bearer of rights.

Furthermore, there are more principles in the juvenile criminal proceedings, namely: “minor offensiveness” whose aim is to favour the minors’ quick exit from the justice system, without interrupting their educational processes; “suitability”– the juvenile criminal procedure must be suitable to the minors’ personality and to their educational needs; the principle of residuality of detention; the principle of non-stigmatisation and the right of the minor to be constantly informed on the meaning of any procedural activities as well as of any judicial decisions.

These principles are effectively applied with the introduction of measures intended exclusively for minors, including non-custodial pre-trial measures – prescriptions, placement under home confinement, and placement in the community. Hence, they avoid the impact on the minor in the pre-trial phase and allow the execution of a community measure during which the minor is entrusted to the juvenile justice services.

In addition to the non-custodial pre-trial measures, there are two other innovations which have completely changed the way the justice system addresses the deviance of adolescents, which are “Non-suit upon Legally Irrelevant Facts”, and “Stay of Criminal Proceedings with minor’s placement under probation”. The first one provides that the Public Prosecutor, during pre-trial investigations, shall ask the Judge to enter a non-suit upon legally irrelevant facts when proceedings would prejudice the minor’s educational needs, if continued, according to the above-mentioned principle of minor’s offensiveness.

The second represents a strong innovation in the Italian legal system. The successful overcoming of the probation period, which lasts a maximum of three years and can be granted for any crime, involves the extinction of the offence and not just the extinction of the penalty.

The results obtained during these years of application of the Presidential Decree 448/88 are very encouraging: the number of probation measures has had a steadily growing trend and the desired results, including the main one for residual detention, both in the pre-trial phase and in the execution of the sentence, can be considered as having been achieved.

Moreover, recently (at the end of 2018), the approval of the new juvenile penitentiary law introduced new community measures for minors, in addition to those already existing, which shall make the recourse to measures depriving personal freedom for minors more and more residual.

JT: To what extent does your Department take advantage of technological developments to achieve greater efficiency?

GT: In fact, since 2010 the Department has used the SISM -Information System of Juvenile Justice Services – for the management of information related to minors. This system allows the dissemination of information relating to the minor’s files among the Central administration, the juvenile justice social services and the judiciary. This system is a single database or file collector, which can be accessed upon authorisation. This enables the acquisition and management of information on minors and young adults in charge of the juvenile services and speeds up the exchange of information between the various professionals who work in the juvenile services and juvenile courts.

Moreover, through this information system, we can obtain data that are then processed anonymously through a specific business intelligence application for the statistical analysis and the construction of “information dashboards” of the CIS system – Statistical (interactive) Information Dashboards – at the disposal of the Central Administration and all the juvenile services.

JT: Currently, the phenomenon of violent radicalisation is a pressing topic as it occurs not only in prisons but also in the context of community sentences.

What is your Department’s approach to the phenomenon of radicalisation and violent extremism?

GT: The Administration pays constant attention to the issue of radicalisation and violent extremism. Furthermore, we cooperate with the Department of Prison Administration, through the implementation of the European project RASMORAD P&P on the prevention of violent radicalisation in prison and probation settings.

The activities of prevention of radicalisation and violent extremism within prison and probation services are carried out through direct collaboration with the Committee of Strategic Counter-Terrorism Analysis, at the national level, as a permanent forum between the judicial police and intelligence services and as an instrument for assessing information on the domestic and international terrorist threat.

My Department also issued guidelines aimed at highlighting prevention tasks and, in 2017, provided operational directives on the topic. Decentralised services are called to collaborate in the observation of those potentially at risk, providing constant updating and using indications given at institutional training meetings, such as the European project TRAin Training – Transfer Radicalisation Approaches in Training, under the Justice Programme, which provides for the training of personnel on the knowledge and application of radicalisation risk assessment tools.

JT: For almost 27 years you have worked in juvenile courts (as a prosecutor, judge and then president).

How does that extensive experience influence your job in the present?

GT: I have been in the Judiciary for almost 35 years, and, in some way, the position I currently hold represents a round-off.

My first job, when I was very young, as a supervisory judge for adults focused my attention on the delicate and complex world of the sentences’ enforcement. The changeover to juvenile justice, working in the areas of juvenile criminal deviance and in the civil sector – in the area of the rights in several respects denied to children – represented a fascinating and major challenge which has led me to reflect, also in the light of our Constitution, on the deepest meaning of the penalty.

I carried out the functions of a juvenile public prosecutor, juvenile judge and I chaired a juvenile court, which allowed me to come into contact with all the local contexts getting to know their peculiarities.

My current commitment is not limited to the procedural profile but to the identification of the most appropriate solutions to ensure the effectiveness of the sanction, the protection of society and the concrete recovery/rehabilitation of the offender including through the spreading of best practices and involvement of the community in the offender inclusion programmes.

I am more and more convinced that only through integrated, tailored and widely-shared projects, it is possible to develop successful rehabilitation processes and reduce recidivism.

//

Gemma Tuccilo is the Head of the Department of Juvenile and Community Justice of the Italian Ministry of Justice. She has been a Magistrate for nearly 35 years and almost all her career has been linked to juvenile justice. Between 2010 and 2015 she has been the President of Potenza’s juvenile court and in Naples, she held the positions of Judge (1997-2010) and Deputy Prosecutor of the Republic (1988-1997). She has a Law Degree from the University Federico II of Naples.