Interview

Peter Maurer

President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has a humanitarian mission focused on providing assistance and protecting the lives and dignity of people affected by armed conflict.

The organisation contributes to ensuring humane treatment and conditions of detention for all detainees. President of the ICRC for nearly ten years, Mr Maurer has prioritised strengthening humanitarian diplomacy, engaging States and other actors in respecting international humanitarian law and improving the humanitarian response through innovation and new partnerships.

What is the scope of the ICRC’s mission in terms of supporting those who are involved in the justice system and, specifically, prison and detention environments?

PM: Under its mandate, conferred by the 1949 Geneva Conventions and the Statutes of the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement, the ICRC monitors conditions of detention and treatment of people deprived of their liberty in relation to armed conflicts and other situations of violence.

This covers today about 90 countries worldwide to which we add the visitation to people held by International Tribunals and Criminal Courts.

As a neutral, impartial and independent actor with a solely humanitarian mandate, the objective of the ICRC’s detention activities is two-fold; firstly, to prevent forced disappearances or extra-judicial executions, illtreatment and failure to respect fundamental procedural safeguards and judicial guarantees. Secondly, to ensure that the dignity and integrity of people deprived of their freedom are respected and conditions of detention are in line with applicable laws and internationally recognized standards.

The ICRC aims to access detainees from the time of their capture or arrest and be able to follow their whereabout throughout their detention depending on their situation and sometimes until their release under safe conditions. We actively engage with the relevant authorities to support them to resolve problems relating to detainees needs, which sometimes results in the ICRC providing material assistance to improve the conditions of detention.

The scope of our detention work has expanded due to the “internationalisation” of conflicts, their protracted character, their impact on the displacement of people and the needs of particular groups.

We witness growing trends directly affecting the detention settings we work in, such as growing urban violence, severe drug policies or the worrying consequences of climate change, or today pandemics or other health concerns.

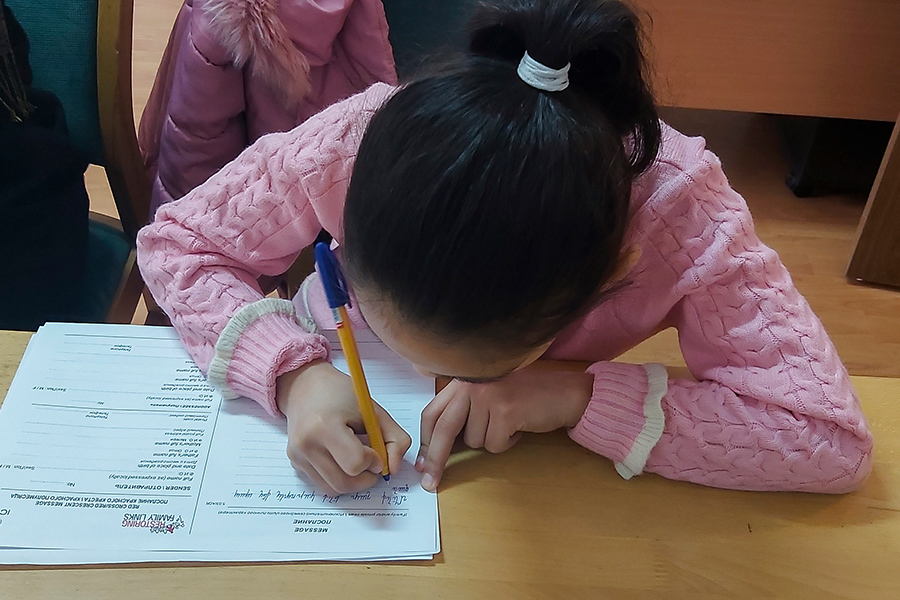

For example, the ICRC undertakes ad hoc detention actions in various European countries hosting people arrested in relation to acts of terrorism or returning from fighting abroad. We also work with our Red Cross and Red Crescent National Society partners especially in detention centres for migrants or in some specific cases in the implementation of family visitation programs.

Importantly our primary focus is on achieving a positive and sustainable outcome for individual detainees. This entails working with stakeholders at many levels starting from the prison or place of detention where the detainee is held, the detaining authorities, at the ministerial level and eventually at the legal framework level.

The range of actors with whom we work and interact goes beyond the detaining authorities. They often include other institutions within the criminal justice system or the national health or public infrastructure systems, as well as professional organizations such as the ICPA or regional associations of penitentiary and corrections services.

With the limitations of the confidential dialogue we have with detaining authorities, we create synergies when possible with other institutions such as the concerned agencies of the United Nations, development, funding and policy actors.

A positive example of partnership was the production of the Handbook on Overcrowding that we developed together with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), or our manual “Toward Humane Prison” we wrote together with a group of multidisciplinary and international experts.

What are currently the main challenges to fulfilling the ICRC’s mandate and mission in prisons and places of detention?

PM: Aside from the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, we face a number of challenges, and many are specific to the contexts we operate in. Most importantly and if to fulfil the objectives I described earlier, we need to secure access to people deprived of their liberty, especially at the early stages of detention.

Then we need to build confidence and, based on a shared problem analysis, develop meaningful conversations not only around respect for the international and national law and standards but also on concrete, realistic and sustainable actions around the humane treatment of detainees, respecting their mental and physical integrity and dignity. But there are other challenges.

Places of detention and criminal justice systems can often be the last priorities for governments and may not be adapted or resourced to fit security policies. The overuse of incarceration and the lack of alternatives to detention increase the many problems associated with overcrowding in prisons.

The authorities, and organisations like the ICRC that support them, face challenges in moving from fixing recurrent superficial problems to bringing concerned stakeholders towards sustainable solutions that efficiently address the root causes of those problems.

The overuse of incarceration and the lack of alternatives to detention increase the many problems associated with overcrowding in prisons.

Can you tell us about the principles that govern the ICRC’s position with the political leadership of the countries where you work? What principle(s) is/are crucial for gaining access and ensuring cooperation?

PM: The ICRC works in accordance with the seven Fundamental Principles of the Red Cross and Red Cross Movement. The most relevant in this context are the principles of neutrality, impartiality and independence which provide the foundation for our humanitarian action and are at the heart of our engagement with all actors.

These principles allow the ICRC to build trust amongst all parties to a conflict and institutions it works with. They enable us to establish and maintain a confidential dialogue with the authorities around humanitarian issues, which is particularly important when negotiating access to detainees and making recommendations.

JT: The COVID-19 pandemic has brought many challenges to agencies and authorities responsible for prisons and places of detention around the world.

To what extent has the ICRC intervened and supported the administrations and ultimately the prisoners and detainees?

PM: The spread of COVID-19 in prisons has presented many challenges. The direct impact on people deprived of their liberty has been considerable, not least in terms of transmission of disease and sometimes death in closed settings.

Prolonged situations of medical isolation are not dissimilar to prolonged solitary confinement and the restrictions on visitations by family members and lawyers, delays to legal proceedings and, in some cases, limited access to food, medical care and rehabilitation programmes, have all had a detrimental impact on detainees’ mental health.

Prison authorities too have faced considerable challenges ranging from staff exhaustion to maintaining a good order in uncertain times, from meeting growing basic needs while facing huge and sudden restrictions in movements and limitations in budgets.

However, COVID-19 has also presented some opportunities. Measures have been taken to decongest places of detention in many countries.

Video calls and other forms of online communication have been adopted to enhance family links and telemedicine has proved a workable approach to medical consultations. However, these approaches should never replace face-to-face family visits or direct access to medical personnel and the judiciary. The principle of normality must be maintained as we define the “new normal.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly affected the ICRC’s detention activities around the world. We carried out fewer monitoring visits to places of detention in 2020 compared with previous years, which has made it difficult to monitor and follow-up on individuals and overall prison conditions.

During the pandemic, ICRC interventions have included actions to prevent the virus from entering places of detention, including screening areas at prison entrances, quarantine centres and virtual family visit areas.

We also undertook mitigating actions to limit the spread and consequences of the virus within detention facilities with the distribution of items that support good hygiene or in supporting building and rehabilitation projects that improved water and sanitation infrastructure and constant improvement of ventilation and environmental cleaning practices.

This has been constantly complemented with advocacy around equal access to COVID-19 vaccines and decongestion measures.

Our visits resumed in several countries in 2021 when all measures could be in place to do no harm to people detained and staff and to ensure the duty of care to our own personnel.

COVID-19 has also presented some opportunities. (…) Video calls and other forms of online communication have been adopted to enhance family links and telemedicine has proved a workable approach to medical consultations.

The 1st World Conference on Health in Detention will take place

in June 2022. What can you tell us about this ICRC event?

PM: The ICRC is organizing this conference, the first of its kind, with co-sponsorship from the World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe and in partnership with the International Corrections and Prisons Association (ICPA), the Worldwide Prison Health Research and Engagement Network (WEPHREN) and the Justice Health Unit of the University of Melbourne.

This ICRC event will bring together a range of practitioners and their managers, including those from government ministries responsible for prisons and prison health, officials from health ministries or departments, academics, public health experts, representatives from international organizations and researchers and specialists from around the world.

The conference will be an opportunity to share experiences, challenges, lessons learned as well as emerging evidence and data, with the aim of ensuring equality and equivalence of care for people deprived of their liberty while also promoting a whole-of-government approach to health in detention.

The conference will focus on various topics around four main themes, which also reflect the ICRC Institutional Strategy 2019- 2024, namely: 1) From policy to practice: People at the centre to improve health for all; 2) Towards stronger health systems in detention; 3) Making the invisible visible; and 4) Embracing the digital transformation.

JT: The virtual reality topic is highlighted on the ICRC website as you are developing virtual environments as a tool to “teach, motivate and maintain universal respect for International Humanitarian Law” (ICRC website: Virtual Reality & Innovation page).

Please tell us about the ICRC’s investment in virtual reality, how you have used this technology in detention settings and with what results.

PM: The ICRC is interested in the great potential of virtual reality as a vector for learning and to change behaviours. Since 2012 that we have been working with the video game industry to introduce a basic level of knowledge of International Humanitarian Law in war games with a particular success in a partnership with Bohemia Interactive Studio that culminated in the release of an additional module (DLC) specifically designed to teach International Humanitarian Law (IHL) to fans of the games ARMA3.

Moreover, the ICRC has been using VR to develop powerful and innovative training tools in various areas related to our work with the armed forces, forensic specialists, in water and sanitation, nutrition, but also for our security and crisis management.

This year, we deployed a new International Humanitarian Law (IHL) training tool for armed forces. It targets both commanders and individual soldiers. The ultimate goal is to provide them with a product that is tailored to their needs, easy to use and free of charge.

Indeed, current commercial training simulations usually don’t include specific legal modules and are often costly. Here, the ICRC aims at facilitating the access and use of this technology for the teaching of international law.

Moving soon from single player to a multiplayer training tool, the next steps will be to connect together members of the armed forces, non-state actors, scholars and ICRC specialists into a shared virtual reality experience as a complement to ICRC’s traditional formats of IHL training and promotion in field operations.

Within the framework of detention, the ICRC started in 2017 to use VR technology as an advocacy tool with the judiciary to sensitize them by visualizing the consequences of overcrowding and how their judicial decisions could have a positive impact.

Building on an early development of a virtual prison and training videos at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, we further developed a Virtual Prison Multiplayer simulation.

It is designed as a training tool, allowing coaching and mentoring sessions for professionals involved in detention work, including ICRC delegates, staff of Red Cross and Red Crescent national societies, national preventive mechanisms, penitentiary schools and academies.

Trainees are able to conduct a full detention visit in a close-to-real prison environment whereby they assess conditions of detention and the treatment of detainees and are able to interact with role-played detainees and prison staff.

In order to address the digital and connectivity gaps and reach out a larger audience, web-based versions are being prepared that will enable prison staff, civil society organizations and students, not yet equipped with the required technology and in-house support on detention issues, to benefit from an immersive 2D experience in a detention environment.

In addition, we are looking at developing additional VR products covering issues such as specific vulnerabilities, the management of the food chain, overcrowding and the provision of health care in detention.

Designed both as sensitization and training tools, it would be possible to use them on a self-pace mode or during training sessions. Trainees would use pop-up interactive menus on specific issues in detention, the applicable legal framework, or on options to consider when addressing these issues.

Contributing to the training and development of prison staff is one of the key components of ICRC’s efforts toward improving detention systems.

JT: There is no doubt that the training and development of prison staff is critical to supporting institutions to observe the law, including international humanitarian law.

To what extent and how does the ICRC intervene at this level?

PM: Contributing to the training and development of prison staff is one of the key components of ICRC’s efforts toward improving detention systems. Complimentary to its monitoring activities and broader dialogue on detention issues with detaining authorities, the ICRC supports them in many ways including through ad hoc training to detention managers and staff on creative solving of humanitarian issues it observes during its visits.

In several instances we support penitentiary schools in updating their curriculum, modernizing their training materials towards e-Learning or translating in local languages existing material such as the UNODC e-Learning on Nelson Mandela Rules.

What would be the main message you would like to address to Ministers of Justice and heads of prison services of countries in which the ICRC is currently operating?

PM: We would like to convey our appreciation to the countries in which we are operating and for the levels of meaningful engagement and cooperation that we have enjoyed thus far.

There is a growing number of actors working in detention, each with its own framework and working modalities, and often with great complementarity.

In this sphere, the ICRC is placed as a relevant and trusted humanitarian organisation and be able to work according to its methods primarily for the benefit of people detained but also the staff, the visitors and ultimately the community.

As the international community approaches the deadline for reaching the sustainable development goals, including the SDG 16 on Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions, we still see too often that places of detention remain the dark holes of societies, too frequently left aside in public investments policies, with incarceration used without looking at alternatives.

At a national level in our confidential dialogue, in regional fora, and more recently during the Kyoto Crime Congress earlier in 2021, we consistently call on States to respect their commitments and obligations including their legal obligations under international and national laws.

And in addition, we remain concerned that political solutions must be found to address the plight of populations caught in limbo, those detained in situation of arbitrary detention, those far from home without the right to fair trial, facing excessive lengths of pre-trial detention or those that should be diverted from detention due to their inherent vulnerability.

Peter Maurer

President of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC)

Peter Maurer studied History and International Law in Bern, where he was awarded a doctorate. In 1987 he entered the Swiss diplomatic service, and his career includes missions to the United Nations. Moreover, from 2010 to 2012, Maurer was Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, overseeing the Swiss diplomatic missions around the world. Since taking over the presidency of the ICRC on July 1, 2012, Mr Maurer has led the organisation through a historic budget increase.