// Interview: Stéphane Bredin

Director General of the Prison Administration, France

JT: What is the situation resulting from overcrowding and what is being done to address it?

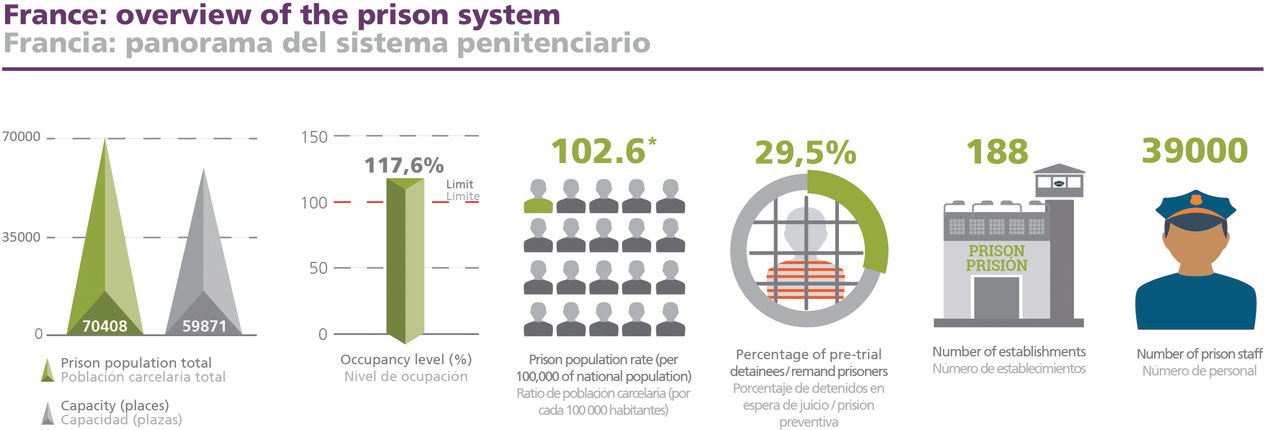

SB: We are still among those southern states of Western Europe that have very high rates of overpopulation. The national average rate of occupancy is almost 120%, but this rate masks extremely strong disparities, because in the so-called arrest houses (maisons d’arrêt) — i.e. the institutions that accommodate prisoners who are not yet on trial and prisoners sentenced to short sentences—overcrowding exceeds 140%.

In total, it is estimated that there is an excess of approximately 14,900 inmates. Some are subject to difficult prison conditions: there are 1,687 mattresses placed on the floor and only 39% of the inmates live in individual cells. There are many reasons for this: we do not have enough facilities and the criminal population has been growing steadily over the last 40 years. This situation is exacerbated by the fact that 30% of our 70,600 detainees are charged.

The responses we are trying to implement include two approaches: increasing the capacity of our penitentiary institutions and implementing a criminal justice policy to reduce incarceration through the bill that the Minister (of Justice) will present to Parliament in the autumn.

This is the first time that these two steps have been taken at the same time: we have carried out an impact assessment and an estimate of the effects of the penal reform and, as a result, the number of sites to be built is based on the increase in the criminal population that we expect in the next ten years.

With this penal reform, we join an international movement whose philosophy is to decentralise our system of sentences from the imprisonment one.

In the real estate sector, we have new means in relation to previous programs: we have created a needs map and the mayors were asked to find locations to build prisons. In addition, the bill includes new legal provisions to accelerate construction. We also established the priority of building prisons again in urban areas (and not in rural areas, as was so often done in the early 1990s) to avoid access problems and to facilitate the creation of partnerships with associations and other services.

We want to build prisons that really promote the reintegration process. We will even count on—among the future constructions—smaller facilities (90 to 120 places), in contrast to the prior trends in France. In the next 5-6 years, the first 7,000 places will be delivered. The new facilities in the city will have a lower level of security, and the detention regime will focus on the autonomy of the detainees and, therefore, on the preparation for their release.

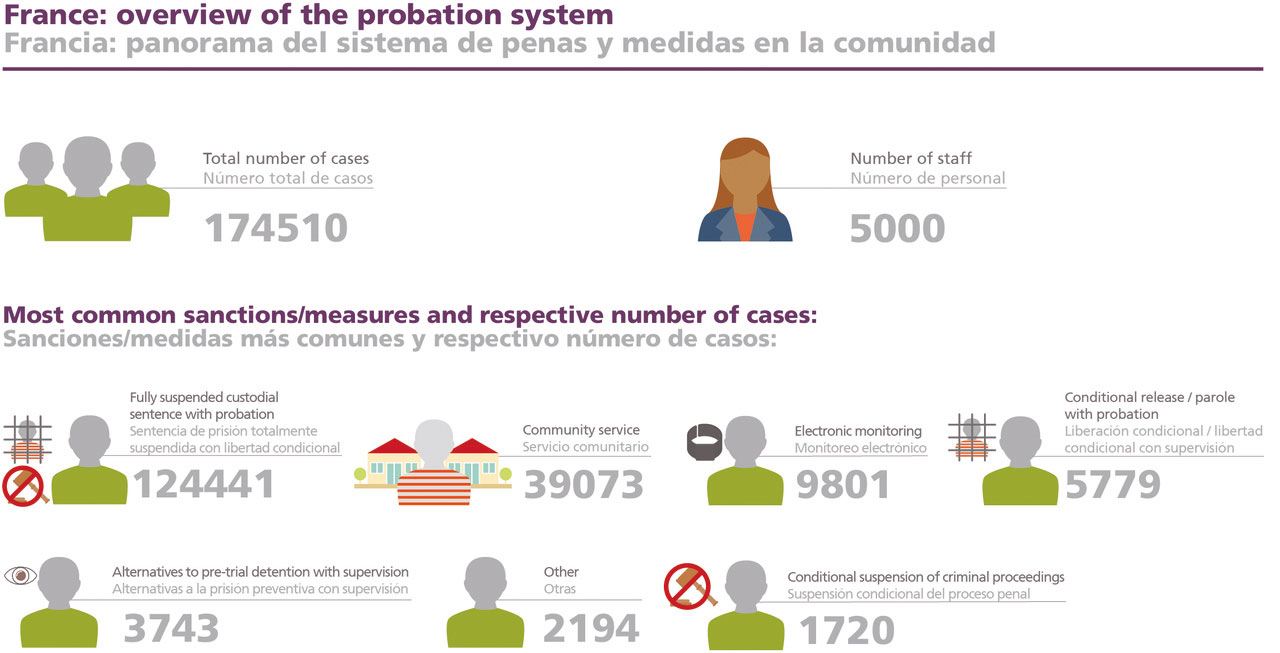

In another aspect of this penal reform, we join an international movement whose philosophy is to decentralise our system of sentences from the imprisonment one, that is, a perspective where the prison sentence is not the only model around which to build all the system. The name “alternative sentencing” illustrates well the fact that the standard is still jail.

In fact, probation sentences (in France) are an extremely recent development. I believe that even in the minds of the courts and judges, these sentences are not always perceived spontaneously as “equal” to imprisonment. The whole philosophy of this penal reform is based on saying that there are several sentencing alternatives and that they are all the same: they must simply be adapted to the convicted person’s profile and their crime.

The penal reform provides for the abolition of sentences of less than one month’s imprisonment. This sends a strong political signal: it states that short sentences make no sense in terms of reintegration and prevention of recidivism, as they have all the negative effects without any positive ones. For sentences of two to six months, the new law states that the principle is to pass other sentences, such as community service, probation or electronic monitoring; the idea is that the sentence shall be executed in the community, with improved supervision carried out by probation services.

Sentences of up to six months’ imprisonment must be subsidiary, i.e. they must be passed in cases where the judge considers that, despite everything, such a sentence makes the most sense. For sentences of six months to one year, the judge still can immediately change them (aménagement “ab initio”) to electronic monitoring, community work, suspensions with judicial follow-up, etc.

[To address the issue of mobile phones in prisons] We have acquired a solution whose jammers will evolve according to the technologies used by the telephone companies.

JT: There is a plan to install 50,000 telephones in French prisons. (Source: Le Figaro, “In prison, landlines for each cell”, 02/01/2018).

What challenges is the prison system trying to overcome with this investment?

SB: We have many mobile phones being smuggled in, illegally, and that poses a number of security problems, as they allow criminal activity to continue and because they generate trafficking and violence. To give you an idea, in a prison built a few years ago in the south of France — a very safe prison and where it is difficult to get mobile phones —, a mobile phone was being rented for €1500 a month.

The jamming solutions we procured are working today, however, the problem with it is the lack of devices that work in the long term, i.e. every time operators change their technology and frequency (every 3-4 years), and the jammers become obsolete. To combat this problem, we need progressively more effective signal blocking solutions, and we need to start with the establishments with the most contraband (the Paris, Lyon and Marseille regions).

Thus, we have acquired a solution whose jammers will evolve according to the technologies used by telephone companies. We have several tens of millions of euros to cover a maximum number of facilities over the next four years, starting this year with several large establishments.

At the same time, we will be installing landlines. The State will financially support this acquisition, and, in turn, landlines will be installed through a public service concession: a company will invest in the installation and the service will be funded by the prisoners, who will pay for their communications.

Today, detainees can only call from the booths until five o’clock in the afternoon. In addition, we have negotiated a decrease of over 50% of the price of communication services so that prisoners can afford them.

JT: France has a suicide rate of 43 per 10,000 detainees, while the average in Europe is 18. (Source: SPACE I report, 2016).

How does better communication between detainees and their loved ones help to reduce suicide rates?

SB: Although this is a very serious situation that worries us greatly, the truth is that it has improved considerably in the last decade: about ten years ago, we had an average of 125-130 suicides; now there are 100-110, of which 97 occurred in prison and the others at the hospital.

In fact, we have reduced the number of suicides in prison even though overcrowding has continued to increase. To begin with, all levels of the prison administration have been mobilised and there is a very strong awareness that has really engaged all the staff. Our policy focuses on three priorities: prevention, protection of inmates in the event of a suicide crisis and the fight against feelings of isolation.

About prevention, we have further developed the prison officers’ training in order to improve observation and detect suicidal crises. We also promote the exchange between professionals, not only the officers, but also other practitioners, the sentencing judge, medical services, probation services, etc., and so we have optimised the information flow.

Then, we have focused our attention on the moments that we identify as the most dangerous (especially at arrival, during the first days in prison and when the detainees are transferred to the disciplinary wing, that is, when they are sanctioned). We have also developed, together with the French Red Cross, a programme called “Support Detainees”, that is, detainees we have trained to listen to other prisoners.

In addition, many establishments have special protection cells where detainees can be housed at the time of a suicide crisis. In the same way, one of the ways to fight against the feeling of isolation is through the telephony installed in the cells, which will allow detainees to also call their loved ones at night. Additionally, detainees can call support services for free through the existing telephones.

JT: There are people who criticise the archaic management of the penitentiary system, which supposedly is lacking a digital revolution (Source: Le Monde, “Prisons suffer from outdated management”, 29/06/2017).

Are there plans to introduce more technology? And how can digitalisation improve the results of the penitentiary system?

SB: We have been thinking about this project for two years and it has political support, including support from the Ministry of Finance. We want to take advantage of technology to facilitate the work of prison officers and encourage the autonomy and integration of prisoners and their families.

Because of this, for example, we want to develop online appointment scheduling for classrooms (currently, everything is done in person or by phone).

We also expect to provide access to digital services and work with inmates on digital exclusion, for example by giving them access to online training content. In addition, nowadays the system of access to canteen products is very complicated — it requires a lot of money and time for everyone —, so, the idea is to completely digitise this process and allow the inmates to order the products directly through a dedicated terminal.

JT: How is the problem of violent radicalisation and terrorism addressed in the correctional system?

SB: The case of France is very special because we have 500 Islamist terrorists, either in preventive detention or already sentenced. There are also 1,200 individuals who, despite not being prosecuted or sentenced for terrorist acts, are identified as radicalised, in widely varying degrees.

We know that they are radicalised either because intelligence services have warned us or because our services have identified them as such in prison: in April 2017, a penitentiary intelligence service was created, the “Central Penitentiary Information Office” (the BCRP, for its French acronym: Bureau Central du Renseignement Pénitentiaire).

In addition, we have developed the ability to evaluate radicalisation: a terrorist or radicalised prisoner is considered dangerous because of the risk of radicalising other prisoners (proselytism) or the risk of acting against the prison officers or other prisoners, as well as the risk of preparing an attack from prison, etc.

Today, we have four assessment wings, and, at the end of the year, there will be six, so we will be able to evaluate 200-230 detainees per year.

We have 500 Islamist terrorists, either in preventive detention or already sentenced, and 1,200 individuals who are identified as radicalised.

Detainees are monitored over a long period of time by multidisciplinary teams including directors, officers, trustees, psychologists, psychiatrists, educators, social workers, researchers, external speakers and Muslim chaplains.

At the end of the evaluation period, a very detailed summary of the subject is made (behaviour, value system, use of violence, analysis of tendency to act out, relationship with religion, risk of proselytism, etc.).

Once the detainees are out of the evaluation wing, there are three possibilities: 1) the ones with the most dangerous profiles, which show a maximum risk of violence or proselytism, are set aside and segregated (Abdeslam Salah, one of the perpetrators of the attacks of 13 November 2015, is in solitary confinement); 2) the ones with less dangerous profiles, whose evaluation proves that they are low-risk inmates, have a normal detention experience that allows them to work on their socialisation, reintegration, etc. like other detainees, but, of course, they are subject to special monitoring, particularly carried out by the prison intelligence service; and 3) the prisoners for whom there is a risk of proselytism, but whose case is considered to be manageable, are sent to other units that deal with radicalisation.

This is very expensive in terms of human resources because we implement actions alongside teams that span several different disciplines, including stakeholders from associations, imams and others. The aim is to work towards a disconnection from violence, the so-called disengagement. The principle of disengagement is that one does not discuss beliefs (even the most rigorous), but rather, one evokes the relationship that may exist between religion and violence.

//

Stéphane Bredin was appointed Director General of the Prison Administration in August 2017. He is a graduate of the National School of Administration (ENA, France), furthermore, he holds an engineering degree in Economics from the Centrale Paris, and a Master’s in Public Service from the Sciences Po. Stéphane Bredin has held numerous positions within the French Ministry of the Interior and then the Ministry of Justice including Chief of Staff and Head of Department.

Advertisement