Interview

Raphael T. Hamunyela

Commissioner-General, Namibian Correctional Service

Our interviewee joined the Namibian Correctional Service in 1994 as a prison officer. Over the years he has worked his way up through the ranks, having become Commissioner-General in 2014. Nearly thirty years of service have resulted in a comprehensive view of the agency’s evolution. Mr Hamunyela assisted and was part of the organisation’s reform efforts to become modern and rehabilitation focused.

What are the marked differences since you started your career at the Namibian Correctional Service?

RH: Before Namibia’s independence in 1990, under the colonial era, the prison service used to be an oppressive institution. It was, therefore, infamous in the eyes of the public. There were also no rehabilitation programmes, and the emphasis was on prison security and punishing the convicts.

When I joined the institution in 1994, it was known as the Namibian Prison Service. In 1995, it became a fully-fledged Ministry of Prisons and Correctional Services. The then President of the country, Dr Sam Nujoma, decreed prisons should rehabilitate those in their custody.

The replacement of the Prison Law of 1959 by that of 1998 ushered in a new model for the treatment of prisoners, which also aimed to move away from retribution to reformation. Prisons were transformed into learning and corrective institutions.

By then, we committed to complementing our new correctional approach with robust networks, benchmarking, and training.

In the late 90s, the Namibian Prison Service joined international sectorial associations, namely the African Correctional Service Association (ACSA) and the International Corrections and Prisons Association (ICPA). As a result, we learned about best practices and established partnerships with countries and organisations that helped us incorporate these practices and train our officers in managing all the changes.

In 2008, the Namibian Prison Service adopted the Offender Risk Management Correctional Strategy (ORMCS). We adapted this modern evidence-based approach to the Namibian population profile. Among the many changes this new approach has brought, we recruited specialised staff, including psychologists, social workers, teachers, priests, artisans, etc.

At that point, we figured that the traditional administration of offenders could not keep up with the modern correctional approach that we had introduced. That is why the development and subsequent introduction of the Electronic Offender Management System (OMS) was a significant milestone because it allows the collection and generation of reliable and accurate offender information.

In 2012, the old Prisons Act was repealed and replaced by the new Correctional Service Act. This new legal framework complements the modern correctional approach and strengthens its management and operations. This Act also brought in new terminology, more in line with the rehabilitation and reintegration framework.

We took on a Prison Service that was negatively perceived; therefore, we had to build public confidence and garner their support. As such, we introduced several public engagement efforts and strategised on public awareness and education campaigns. These efforts have benefited the NCS tremendously, as we received support in various ways, be it rehabilitation programmes, officers’ training, sponsorships or donations.

The other important aspect is our success in food self-sufficiency.

Agricultural and livestock production are inmate engagement programmes in several correctional facilities. Today, we depend on our produce to provide a balanced diet to inmates, in three meals per day.

Moreover, our production levels make it possible also to supply food to the national police to feed detainees and even sell to the Government at a reasonable cost.

I have been with the NCS for over 27 years, so I have been part and parcel of its transformation. Today, we offer effective rehabilitation and reintegration programmes, thereby significantly contributing to public safety outcomes.

The traditional administration of offenders could not keep up with the modern correctional approach that we had introduced. That is why the development and subsequent introduction of the Electronic Offender Management System (OMS) was a significant milestone.

JT: NCS’s vision is to be “Africa’s leader in providing correctional services”.

To what extent and how is the organisational vision being achieved?

RH: We must measure our success by looking at the extent to which the NCS has achieved its mandate. Moreover, our image and reputation in the country and the continent are also influential.

In terms of safe, secure and humane custody, amongst other measures, the NCS has established an Integrated Security System comprising of CCTV and access control systems for correctional facilities. This system enhances our ability to prevent escapes and other untoward incidents.

The NCS imparts training in critical and emerging security challenges annually to complement these efforts. Our goal is to keep officers refreshed and informed on new procedural, physical, dynamic, and intelligence security methods. Another safety and security measure relies on constructing and converting correctional facilities to accommodate Unit Management. Unit Management allows for smaller, manageable units that are more controllable.

This management approach enhances dynamic security, close supervision, interaction with inmates, and better classification according to inmate profiles.

An important factor in safe and humane custody is also in the ability of the NCS to provide a compassionate, healthy and hygienic environment to inmates. Central to this is health safety. In this respect, we have established health facilities within all correctional facilities.

Moreover, we have recruited healthcare personnel, doctors, and nurses. We offer better salary grades than their counterparts outside the Correctional Service. Our Health Policy is rooted in the principle that correctional health is public health. We consider that inmates must have the same or even better access to health services as the public.

To bring correctional facilities to adhere to international standards, we conducted an assessment with UNODC.

The aim was to understand the extent to which our correctional facilities comply with the provisions of the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners. We have long and short-term strategies in place to bring our institutions closest to treatment standards.

Therefore, we have made infrastructure conversions to meet these standards. Furthermore, any new prison facilities to be built will meet international norms.

Another critical aspect of safe and humane custody is food security. For this purpose, the NCS introduced agricultural food production with a dual objective of rehabilitation and food self-sufficiency, i.e. piggery, animal husbandry and crop production. These activities curtail inmate idleness, teach them agricultural skills and contribute to food security and the country’s economy.

Our efforts have yielded positive results. We monitored 9 186 offenders who were conditionally released (parole and remission) into community supervision between December 2016 and September 2021. Only around 250 (2.73%) were re-convicted, which illustrates a very low re-conviction rate. In addition, we also similarly monitored 12 705 offenders who were released unconditionally between April 2017 and September 2021 and 426 (3.35%) of them re-offended.

Again, this illustrates that our rehabilitation programmes are effective, particularly if comparing our re-offending and recidivism rates with other jurisdictions globally.

To bring correctional facilities to adhere to international standards, we conducted an assessment with UNODC. We have made infrastructure conversions to meet these standards. Furthermore, any new prison facilities to be built will meet international norms.

What challenges are there to overcome in pursuing the NCS’s mandate?

RH: Our biggest challenge remains financial constraints that pose a myriad of shortcomings in many areas. Because of the lack of adequate funding, we have not recruited enough custodial staff to maintain proper security in correctional facilities. Our organisational structure is filled only with about 30% of its staff establishment. This situation can lead to untoward incidents in our facilities; the ratio of correctional officers to inmates is low, and the work overload is stressful for officers.

Lack of finances has also impacted many other critical areas, such as providing necessities and cleaning materials, essential for maintaining hygiene amongst inmates and their living conditions.

Another challenge is the ageing infrastructure that needs constant renovation and increased security equipment. Moreover, we require new correctional facilities, specifically in regions where none currently exist.

JT: The Offender Risk Management Correctional Strategy (ORMCS) is highlighted on the NCS website.

What is this approach, and what are its practical effects?

RH: Our Offender Risk Management Correctional Strategy (ORMCS) is an evidence-based approach that hinges on managing inmates according to their risk factors. Our Rehabilitation and Reintegration Sub-Department is responsible for its coordination and success.

An effective ORMCS has multiple and mutually interacting components that work towards a common goal: to manage, control, rehabilitate, and successfully reintegrate offenders into the community. One of these components is the Reception and Initial Offender Assessment.

We established a systematic approach of processing newly sentenced inmates into the correctional facility. It facilitates their timely assessment of immediate needs, including physical, mental health, and personal concerns. Inmates are also oriented to the correctional system’s rules, conditions, and entitlements.

Another feature is Objective Security Classification and Re-Classification of Offenders; our system includes two assessment instruments to predict inmates’ security risk. The classification instrument determines inmates’ initial security placement in the correctional facility, while the reclassification tool defines the subsequent security levels.

The reclassification instrument facilitates movement from one security level to another. A privilege system is attached to the security levels to serve as an incentive for inmates to progress from one security level to another and encourage them to behave more pro-socially.

Unit Management is another segment currently implemented in most of our correctional facilities. The NCS has made significant strides in making substantial infrastructural changes to the old facilities and constructing new ones to accommodate this modern correctional practice.

Assessment of Risk and Needs of Inmates and the Correctional Treatment Plan is also an element of our offender management strategy. Risk/needs assessment is essential for identifying inmates’ criminogenic needs. Identifying needs and concerns allows reaching an individualised Correctional Treatment Plan that guides inmate management in preparation for release.

Moreover, the delivery of evidence-based programmes to address specific criminogenic needs is a central component of the ORMCS model. Rehabilitation programmes delivered to inmates also aim to support various concerns relating to adjustment and reintegration.

These programmes are structured, cognitive-behavioural based and seek to improve skills deficits in multiple areas. We promote various programmes, namely: Motivating Offenders to Rethink Everything (MORE); Managing My Substance Use (MMSU); Gender-Based Violence (GBV); educational and vocational training programmes.

Concerning the management of inmates with mental illnesses, we have two facilities that accommodate these inmates, separated from the general inmate population. This allows for the effective management and treatment of their unique needs resulting from diminished mental capacity.

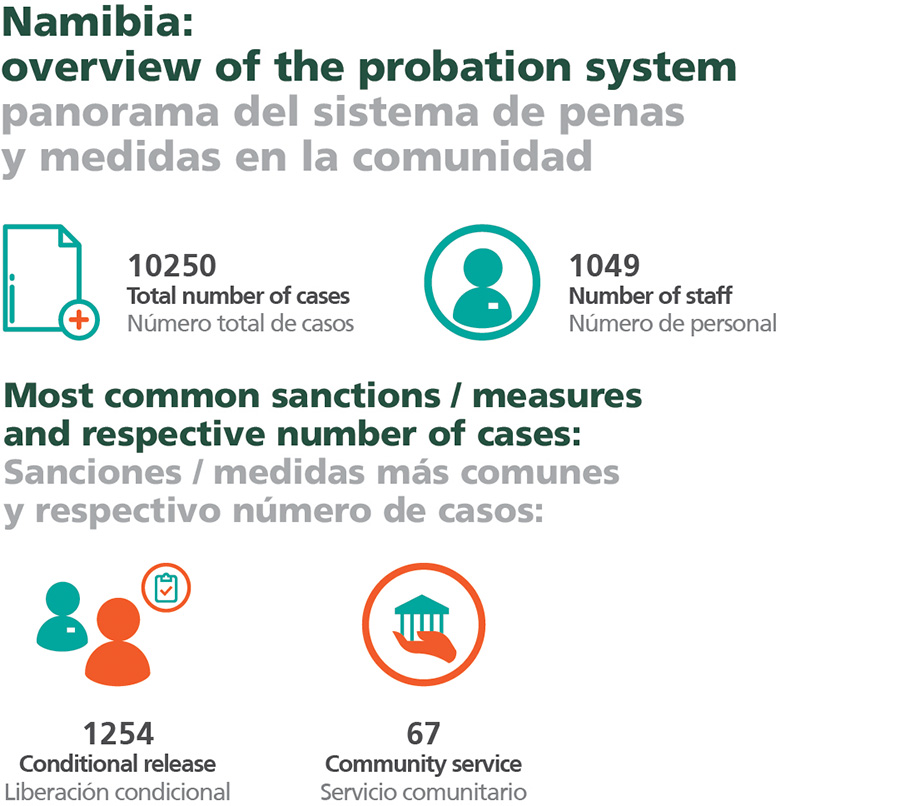

As regards community corrections, we have community supervision and community service orders. In community supervision, we monitor inmates who have been released on parole or remission whether they comply with their conditions of release.

Community Service Orders are alternative sentencing to individuals who committed non-serious offences. The NCS is currently responsible for the supervision of these offenders as well.

Our Offender Risk Management Correctional Strategy (ORMCS) is an evidence-based approach that hinges on managing inmates according to their risk factors.

What role do offender rehabilitation programmes play? And to what extent is external and community cooperation important in supporting these and other NCS programmes and projects?

RH: Offender rehabilitation plays a vital role in imparting cognitive skills that change their behaviour, averts boredom in correctional facilities and thus minimises untoward activities amongst inmates.

Programming enables inmates to gain educational and industrial skills that they can harness once released. Our programmes largely contribute to making them employable and avert crime due to poverty.

The NCS couldn’t be successful or effective without community involvement. As the saying goes, “it takes a village to raise a child”; I believe it takes a community to rehabilitate and, especially, reintegrate an offender.

The community’s role in the rehabilitation and subsequent social reintegration process cannot be over-emphasised. Collective efforts range from individuals and organisations assisting the NCS with any training programmes or constructive activity for the benefit of inmates and officers, to visits and support of inmates by family members, relatives and friends.

Beyond institution-based activities, the community plays a big part in how we accept offenders back to it; how we treat them, and the support we give them. This support includes employment, training, counselling, constructive advice and sometimes the basics of housing and other needs.

In underlining the importance of community involvement, the NCS has numerous agreements with governmental and non-governmental organisations.

Many of these entities have assisted the NCS in many ways, particularly with rehabilitation and reintegration programmes.

The NCS also introduced the Community Advisory Committee (CAC), which comprises community members who serve as an advisory body to the correctional facility within their vicinity. These Committees ensure community involvement in the administration of correctional facilities, inmates’ welfare and serve as a bridge with the public.

The LSMCS Training College serves as the Centre of Excellence for the NCS. It is one of the most modern designed training colleges in Africa.

In collaboration with ACSA, there are plans to turn the college into an African Correctional Service Academy.

JT: The NCS has had a training college for over fifteen years.

What can you tell us about the importance, achievements and challenges around staff training and development at NCS?

RH: We recognise training as an essential component in modern corrections and best practices. For this reason, we have a Human Resources Development and Training Directorate, of which the Lucius Sumbwanyambe Mahoto Correctional Service (LSMCS) Training College is the most fundamental part.

The LSMCS Training College serves as the Centre of Excellence for the NCS. It is one of the most modern designed training colleges in Africa and an enormous pride for our Department and the Ministry.

The primary function of the Directorate is to strategise and develop policy to ensure the capacity development of staff. The fundamental responsibilities of the Directorate are to coordinate and monitor the various training courses as per the Departmental training programme and manage officers on tertiary studies and other courses.

This must be guided by what is best for the Department while considering officers’ individual choices and career paths.

So far, the LSMCS Training College has delivered around thirty Correctional Basic Training courses. The aim is to prepare correctional officers to work within a high-risk environment. At the same time, they need interpersonal skills and fitness to deal with situations.

In collaboration with ACSA, there are plans to turn the college into an African Correctional Service Academy. The Academy will deliver courses to Africa’s various levels of correctional/prison/penitentiary staff from middle management to senior and executive levels. Moreover, it would issue accredited qualifications.

Covid-19 has exposed us to many lessons. Both Government and private entities connect and support each other much better now and use resources sparingly.

What has it been like to lead and manage the NCS in times of pandemic? What challenges and opportunities has the public health crisis brought to the correctional service?

RH: Dealing with the Covid-19 pandemic has presented many new challenges.

Since the pandemic’s started in 2020, the NCS had to make some tough decisions to preserve the lives of both officers and inmates. At a point, we had to minimise the number of staff within our correctional facilities; suspend and minimise rehabilitation and other constructive activities, and suspend family visits.

Another critical area that has been affected is international relations, halting travels in and out of the country and averting global, continental and regional forums.

It is unfortunate because these forums have brought significant returns to the NCS over the years. Through them, we were able to establish benchmarks concerning rehabilitation, security, food production, and many other areas.

The worst of all is that we have lost ten officers and six inmates.

Covid-19 continues to challenge our ability to deliver our mandate effectively. Even with the high number of our officers and inmates vaccinated, there is still an increased risk of infection in correctional facilities.

As the epidemic waves follow one another, many changes that we had to implement remain.

However, our healthcare personnel, and those from the Ministry of Health and Social Services, have done a splendid job in keeping the virus under control in correctional facilities.

I recall sometime this year when the Minister of Health and Social Services expressed his gratitude to the NCS for the way we managed the virus.

However, I also believe that Covid-19 has exposed us to many lessons. Both Government and private entities connect and support each other much better now and use resources sparingly. We have discovered the strength that is hidden in working together.

Moreover, I am proud to note that both the inmates and correctional officers have responded well to the Government’s vaccination campaign.

Raphael T. Hamunyela

Commissioner-General, Namibian Correctional Service

Raphael T. Hamunyela joined NCS in his twenties, in September 1994, as a prison officer. He has worked in many areas within the organisation before being promoted to Chief Prison Officer in 2001. Five years later, he worked at NCS’ Headquarters legal office when he enrolled as a law student at the University of Namibia, a degree that he completed in 2008. Since then, he has been successively promoted, first to Superintendent, then to Assistant Commissioner until, in 2012, he was promoted to the position of Deputy Commissioner-General. He obtained a Diploma in Public Administration and Management in 2013 and the following year was appointed Commissioner-General.