Context

Almost everyone in the United States uses a computer, smartphone or another form of technology, daily, to work, access information, and communicate with others. Knowing how to use a computer, research online, email and create spreadsheets are just a few of the 21st century digital skills that many of us take for granted as requirements for thriving in today’s workplace.

Yet, according to a 2017 survey of 2,000 federal inmates in the U.S., only 3% said they had access to a computer (Ring 2017). This is a particularly compelling number when you consider that many were first incarcerated before computers were commonplace, meaning they have no skills in using them.

If incarcerated people are to re-enter society successfully, their skillsets must include digital competencies and computer literacy. However, prison administrators often bar inmates’ use of technology due to concerns such as security, high costs for hardware and software, and the training required for implementation. They often do not allow inmates to use the internet, citing concerns that inmates might harass people or commit new crimes.

Solution

The U.S. Justice Chapter of the nonprofit World Possible aims to teach digital literacy and reduce recidivism by providing incarcerated students with access to offline laptops and servers. In 2016 and 2017, World Possible launched a pilot programme to reach juvenile inmates in 14 states, with statewide adoption in Oregon, Kansas, Wisconsin, Kentucky, Georgia and California.

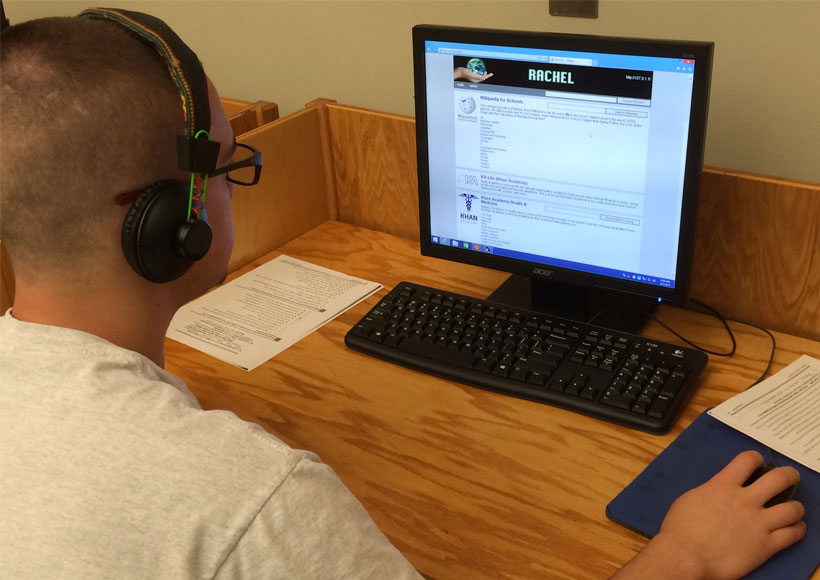

The programme focused on the use of Word Possible’s RACHEL (Remote Area Community Hotspot for Education and Learning) offline technology and Endless Operating System (OS) laptop computers to implement technology without internet connectivity.

Endless OS laptops were loaded with content such as Project Gutenberg Books, K-12 textbooks, and other digital encyclopedia resources, and the Endless software was compatible with Microsoft Office for documents, presentations and spreadsheets. An extensive array of content was also pre-loaded onto RACHEL and Endless OS laptops, including Wikipedia for Schools, Boundless Textbooks, Saylor Academy Courses and Textbooks and Math Expression, to name a few. All of the content made it unnecessary for students to access the internet.

Results

One reason the prison pilots worked was that they included only a small deployment of ten laptops per facility. Planning for deployment was manageable, and the site served as a showcase for peer facilities that wanted to see how the programme worked. Prison administrators were consulted on their choice of deployment location, their target population, and the policies and procedures governing the programme. Teachers and staff within the facilities were given training so they were able to use the technology correctly and efficiently.

Deployment locations included high school classrooms, special education units, behavioural units, regular living units, and individual use by college students. Giving the facility the choice of how to deploy the machines was important for showing the variety and potential of their application. The success of the pilots was demonstrated when state agencies expanded their deployment into peer facilities and into community programmes, with most asking for an additional 140 to 300 machines.

Prison administrators said their participation hinged on the fact that they were not required to collect data during the pilot, which alleviated an additional stress point. Sites did experience positive outcomes with improved student behaviour and academic results. Cursory data indicated a drop in the rate of incidents when laptops were deployed and an increase in reading comprehension. The computers deployed in 2016 are still in use today, and we also recently donated Endless OS laptops to youth leaving the correctional facility, for their continued education.

Research reported by the RAND Corporation shows incarcerated people who participate in correctional education programmes are less likely to recidivate and more likely to gain employment after release (Davis et. al, 2013). In a 21st century workforce that increasingly relies on digital literacy, knowing how to use computers and the internet is a key part of that education. Programmes like the one piloted by World Possible and Endless show that technological access is not only possible for those who are incarcerated, but critical to their success.

//

Frank Martin is the Director of Justice Education at the World Possible. Previously, he was the Education Coordinator for the Oregon Youth Authority, where he held several positions. He advocates the use of technologies through the Corrections Education Association and the Alliance of Higher Education in Prisons. He holds an M.A. degree from the Department of Communication at the University of St. Louis.