Article

Josep García Coll & Pedro Liberado

There is a relatively widespread idea that the imprisonment of violent extremist and terrorist offenders (VETOs) could potentially heighten (the vulnerability risk) of radicalisation across the prison system.

In fact, some reports state that imprisonment by itself could carry some risks in the (further) radicalisation of individuals [1]. However, sometimes these risks have more to do with a tendency to over-estimate the threat of VETOs in prison by prison officers [2] who, for example, have too often equated converting to Islam with radicalising [3].

The Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN) Rehabilitation Manual for first‑line practitioners working with (individuals vulnerable to) radicals(ation) and VETOs [4] highlights the importance of paying special attention to this risk during pretrial detention due to the specificities this period encompasses.

Firstly, inmates have not yet been tried (or received a sentence) and should, therefore, be presumed innocent. Secondly, violent extremism cases tend to receive a lot of media attention, consequently (negatively) influencing public opinion (towards a more securitised perspective).

This can lead prison staff to tendentiously label or stigmatise individuals in pretrial detention with violent extremism/terrorism charges. Therefore, prison staff need to be thoroughly trained to be aware of the principle of presumption of innocence and to try to enhance some sort of professional immunity to popular stigmatisation and media trials of individuals in pretrial detention.

Secondly, because no criminal offence has yet been proven, no specific rehabilitation can start taking place. Thus, the general interventions carried out by psychologists and social workers become crucial at this point. First, they will be in charge of evaluating the risk posed by these newly arrived individuals.

The use of standardised risk evaluation tools is generally recommended to carry out this task, although in some cases professional judgement can provide a more nuanced judgement [4].

On the other hand, they will need to assess the criminogenic needs of the inmate and the possible mental health issues (e.g., personality disorders). This will be important in determining possible interventions to develop with the inmates [4].

Therapists, social workers, and P/CVE specialists (incl. mentors) can already start some of these interventions during pretrial detention. However, in order to avoid reactance to attitude-changing interventions or stigmatisation [4], the activities implemented should never be labelled as P/CVE.

These specialised professionals should also explore the possible pro-social networks that can influence positively the inmate and speak in trial in their defence (i.e., family, friends or partners) [4].

Furthermore, the support of religious representatives is also useful in providing faith-based interventions and moderate understandings of religious practice [4]. Lastly, non-governmental organisations can also be of help in this process.

For example, in some contexts volunteers have proven to be very effective in interventions with VETOs and individuals vulnerable to violent extremism, especially if they share a specific religious, ethnic or linguistic background with them [5].

However, once again it should be noted that any of these possible interventions carried out by these actors should avoid confrontational styles of dialogue with the inmate, in order to avoid reactance [6].

Efforts during pretrial detention will also need to go into ensuring the accused do not accumulate further grievances and are not influenced by other inmates that could potentialise their (already) radicalised viewpoint6. Placement of the inmate can be decisive in preventing these risks.

Sometimes it might be difficult to find a middle ground between establishing the necessary security measures to prevent violent extremists from continuing to carry out their activities and applying containment measures that differentiate inmates for terrorism from the rest. [1; 7-8]

The perception of mistreatment or the victimisation of VETOs that some prison regimes (e.g., isolation) can cause at this point only increases inmate’s own conviction that violent action is justified [3] and greatly hinders his chances to disengage (and, most probably, deradicalise).

On the other hand, experiences with the treatment of VETOs in specific facilities and programming, can also be perceived as a grievance by common inmates [9], and have also impacted public perceptions of prison authorities as rewarding VETOs (e.g., the case of ETA’s members imprisoned in Spain before 1987) [10].

Last, allowing VETOs in pretrial detention to mix with the general population involves specific vulnerabilities to them (e.g. attacks from members of rival extremist groups) [4] and to others (e.g. proselytism and recruitment of other individuals to their cause) [4].

The search for this balance between security and respect for individual freedoms is not easy and finds different practical formulations in each of the inmate management models [11].

In this sense, recent research continues to advocate that defining which concrete model is more effective in terms of preventing radicalisation (or promote deradicalisation) is a challenging and arduous task, due to the diversity of contexts and the lack of systematised information on the success or failure rates for each of them [12].

Nonetheless, as mentioned above, none of these measures and interventions will work without the necessary engagement of prison officers and prison administrators in providing an environment where the stigmatisation and discrimination of VETOs are not present.

Recruitment of diverse teams can be a way to actively prevent this [4]. Also, different experiences have shown the efficiency of dynamic security approaches, which allow evaluating the risks posed by inmates from their daily communication and interaction with prison officers.

Prevention of radicalisation (that could lead to violent extremism) in the pretrial period is crucial due to the specific vulnerabilities present. Therefore, cooperation between different stakeholders both from the prison authorities and civil society organisations is crucial in carrying out this task effectively.

Therefore, effective multi-agency mechanisms will be necessary to carry out the necessary information-sharing and coordination processes present in the follow-up of each VETO.

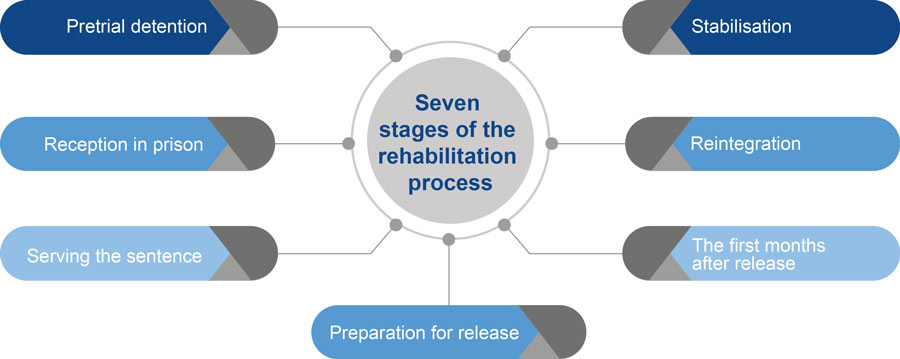

Considering the aforementioned, the MIRAD project aims to enhance the capacity of prison authorities to carry out risk assessment by enhancing state-of-the-art standardised tools, applicable throughout the whole sentencing (and post-sentencing) period.

Furthermore, it incorporates the needs of the different stakeholders involved in the rehabilitation and reintegration of VETOs, by bringing together expert entities and individuals along with prison and probation authorities and non-governmental organisations in newly developed protocols (and tools) aiming to facilitate multi-agency work.

The MIRAD partnership joins public and private organisations who have been selected due to their previous experience in the fields of justice, penological and counter-terrorism research, and education & training. It is composed of research institutions, NGOs, private companies, and sectoral associations working in the field.

The consortium is represented by seven EU Member States that geographically represent Western (France [13-14], Belgium [15]), Central (Poland [16]), Southern (Portugal [17], Spain [18], Greece [19]), and Eastern (Bulgaria [20]) Europe. If you would like to know more about the MIRAD project, please contact us through [email protected] or visit www.mirad-project.eu .

References

[1] Neumann, P. (2010). Prisons and terrorism: Radicalisation and de-radicalisation in 15 countries. International Center for the Study of Radicalisation and Political Violence (ICSR) and National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START).

[2] Schultz, W. J., Bucerius, S. M., & Haggerty, K. D. (2021). The floating signifier of “radicalization”: Correctional officers’ perceptions of prison radicalization. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 48(6), 828-845.

[3] Zahn, M. (2017). Prisons: Their role in creating and containing terrorists. In G. LaFree, & J. Freilich (Eds.), The handbook of the criminology of terrorism (pp. 520-534). Wiley.

[4] Walkenhorst, D., Baaken, T., Ruf, M., Leaman, M., Handle, J., & Korn, J. (2019). Rehabilitation Manual. Rehabilitation of radicalised and terrorist offenders for first-line practitioners (RAN MANUAL).

[5] Orban, F. (2019). Mentorordningen i kriminalomsorgen: En prosessevaluering, Kriminalomsorgens høgskole og utdanningssenter. KRUS University College of the Norwegian Correctional Service.

[6] Braddock, K. (2014). The Talking Cure? Communication and psychological impact in prison de-radicalisation programmes. In A. Silke (Ed.), Prisons, terrorism and extremism: Critical issues in management, radicalisation and reform (pp. 60-74). Routledge.

[7] UNODC (2016). Handbook on the management of violent extremist prisoners and the prevention of radicalization to violence in prisons. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

[8] Veldhuis, T. (2016). Prisoner radicalization and terrorism detention policy: Institutionalized fear or evidence-based policy making? Routledge.

[9] Williams, R. (2016). Approaches to violent extremist offenders and countering radicalisation in prisons and probation. Radicalisation Awareness Network (RAN).

[10] Zuloaga, J. (2021). “Herrera de la Mancha se queda sin presos de ETA”, La Razón, 10 de abril.

[11] Thompson, N. (2018). Australian correctional management practices for terrorist Prisoners. Salus Journal, 6(1), 44-62.12 García Coll, J., & Lobato, R, (2022). La encrucijada entre la radicalización y la desradicalización: Teorías, herramientas y aspectos aplicados. Los Libros de la Catarata.

[12] García Coll, J., & Lobato, R, (2022). La encrucijada entre la radicalización y la desradicalización: Teorías, herramientas y aspectos aplicados. Los Libros de la Catarata.

[13] CNAM Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers

[15] IACFP International Association for Correctional and Forensic Psychology – Europe

[16] PPHS Polish Platform for Homeland Security

[17] IPS Innovative Prison Systems

Josep García Coll

Josep García Coll is a researcher in the area of Radicalisation and Violent Extremism Prevention at the Euro-Arab Foundation for Higher Studies, specialising in violent radicalisation processes and de-radicalisation interventions. He holds a master’s degree in Research in Psychology from University of Barcelona and another in Peace, Conflicts and Developmentfrom Universitat Jaume I. Josep is currently a doctoral candidate in Social Psychology at the University of Córdoba. Before, he has worked on conflict resolution and violence mitigation in different countries. He also co-authored the book “The Crossroads between Radicalisation and Deradicalisation”.

Pedro Liberado

Pedro Liberado joined IPS_Innovative Prison Systems in 2018. He would start coordinating the Radicalisation, Violent Extremism and Organised Crime Portfolio team in that same year. He was nominated as Chief Research Officer two years later. In addition to those responsibilities, he has been a shareholder and member of the Managing Board since January 1st, 2022. Pedro Liberado has a degree in Sociology from the University of Coimbra and a master’s degree in Criminology from the University of Porto. He currently is a PhD candidate in Criminology at the University of Granada.