// Interview: Rodil Hernández

Director General of Penitentiary Institutions of El Salvador

JT: Which are the main challenges that the justice system, in general, and the penitentiary system, in particular, have to face in El Salvador?

RH: In the case of the justice system, the main challenge is, probably, the fact that it should be as our Constitution establishes: a fast and efficient Justice!

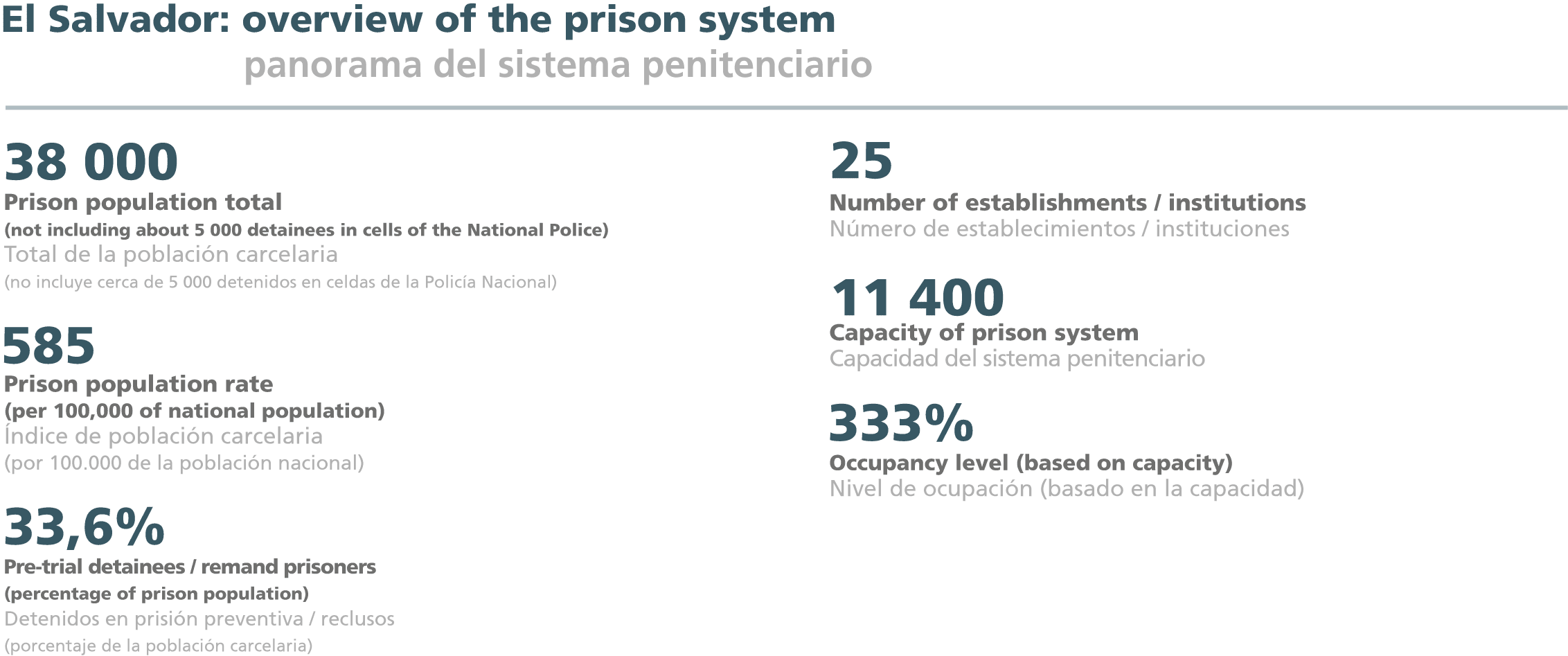

At the penitentiary level, it has improved a lot because we have new courts of penitentiary supervision and execution of the sentence. The main challenge is the reduction of the overcrowding of more than 300%, the highest in Latin America: we have 38 000 people deprived of freedom but our capacity is just for 11 400.

There are 5 000 people who have not entered the system due to a lack of space, so they are in preventive detention in the facilities of the National Civil Police. This is a big challenge, and also the professionalisation of our staff, mainly the prison guards.

We have a very complex issue: gang groups that have been mutating in such a way that they have become transnational structures of organised crime and reach 1/3 of the imprisoned population.

The old infrastructure, that is obsolete and deteriorated due to lack of maintenance, is another challenge, also because it was not designed to be detention facilities, much fewer treatment centres. There are convicts, in our country, who are imprisoned in the same places where horses used to be kept in!

We are now developing a series of investments – of more than 185 million dollars – to create a new infrastructure and workshops for rehabilitation, but also to hire more than 1400 people who will join the staff we already have now, which does not exceed 2600 people.

JT: In 2000, there were 7750 inmates (130 of prison population per 100 000 of the country’s inhabitants); after 16 years, the number of inmates has reached 38 000 and the prison population rate more than 550.

Facing this reality, what is the strategy and which specific actions are you carrying out in order to solve the overcrowding problem?

RH: Firstly, we established an integrated information system. There wasn’t even an automatic counting system! We call this information system “SITE”: it allows us to know who we have and all the legal, personal, demographic, medical, etc. data, all the information that is needed in order to establish a strategy. That database is six years old and, thanks to it, we could know that around ten thousand prisoners were going to serve their sentences within the next 10 years.

We established a strategy of classification, based on the adaptability to the rehabilitation processes. We have a progressive system regarding the serving of the sentences and the strategy to strengthen the system has to do with creating all the structure, physical, of staff, and of treatment programs which can accelerate the progression.

It’s true that around 10 000 people are about to be released, but we can make that the rest of the inmates can obtain any of the benefits that our law provides, such as, the confidence phase, semi-freedom regime, or the penitentiary benefits like ordinary or early parole.

The result we expect, by the year 2019, is to leave the overcrowding rate at 30% over the installed capacity because we will generate 17 400 new spaces.

I am concerned with accelerating the progressive regime and with the qualification of those who are approaching the end of their sentences so that they obtain tools for life and work, knowledge, and treatment so that they can be integrated into the society in a successful way.

This includes all detainees, except those who belong to gangs because the crimes for which they have been convicted have longer sentences. During the next five years, they will follow the ordinary regime, and they (90% of them) will have few possibilities to obtain any of the penitentiary benefits.

Nevertheless, our treatment program if for 100% of the prison population, without any exceptions or differences.

JT: We know that, since 2011, you have a rehabilitation program called “I Change” which, since the end of June 2014, has become a new model of prison management.

Can you please explain what this new model is about and what is the state of play of its implementation?

RH: “I Change” is treatment model in which there’s zero spare time, this means that 100% of the inmates will be integrated in the different programs of treatment or job occupation. We make them get involved in the development of learning programs, working or occupational skills, cultural, spiritual, etc.

The program begins with an awareness of the situation where they are, the recognition of the crime committed and the need of building up a new life project. Then, give them an occupation and help them discover their skills.

There is also a strong working component, through the different activities of maintenance of the prison facilities and community service; we have approached the inmates to society, in a way that they can contribute with municipalities, governmental institutions or with other businesses, under the supervision of tutors.

We also have the support or our legal system which allows the inmates who take part in community services to rectify their sentences, in a way that they can reduce them in 2 days per day worked; many of them can get parole benefits and obtain work tools.

The “Yo Cambio” model has practically become a brand of the system which is known all over the country and has led society to become more flexible… In our country, there was a great “thirst for revenge” in society especially due to the gangs and the problems they cause and have caused to the Salvadoran society with their serious crimes. So, it’s been a process of reconciliation of the prisoners with the society.

With all this, we achieved the reduction of inmates and the organisation of the centres; we have also improved the cohabitation and health standards. Currently, 95% of the detention centres are within the “I Change” management model. There are only three centres left, those which are for gangs (Ciudad Barrios, Quezaltepeque, and the maximum security, Zacatecoluca). We are going to implement this model in these centres within the next two years.

JT: El Salvador is one of the countries facing the problem of gangs and organised crime.

What is your opinion about this problem and the consequences that it brings to the criminal justice system and to prisons?

RH: The gangs are highly organised and well-structured groups. The model also includes the necessary measures to break up their “heads”, who are the ones who push the rest of the members to keep on committing crimes, even from inside the prisons.

We have also taken extraordinary measures in the detention centres where the members of the gangs are kept. These extraordinary measures imply more serious actions to maintain the order, and their objective is to break up these criminal structures in the prisons and in the streets. This policy implies some restrictions which interfere with the inmates’ rights.

Those were measures passed unanimously by the Congress – in our Legislative Assembly 100% of the representatives have voted for them – and they have had an effect of reducing both homicides and crimes of extortion.

The criminal structure has been broken up economically and, within the prisons, these extraordinary measures have isolated the inmates, even by forbidding the visits – only professional visits are allowed. These are drastic measures but necessary to solve the problem with the gangs.

We’re building detention centre of greater security to keep the leaders of these structures and the new management model is already being implemented in three of these six penitentiary centres, where gang members are taking part in the process and their behaviour is changing.

The objective is to reach 100% and to speed up a series of works to improve the infrastructure and design of the detention centres, in a way that we can have a better control and develop the right treatment programs.

We have had a constant relationship with human rights organisations and with the Human Rights Attorney Office, which has unrestricted access to all our prisons.

JT: In April 2016, some special measures came into force in the prisons where gang members are kept. The objective was to isolate them, as they are thought to be the criminal driving force behind the gangs. These measures have been extended for one year more.

What is the state of play, are these extraordinary measures producing the desired results? And what is the situation as far as human rights are concerned?

RH: You really have to know how the criminal structure of the gang works… In 2004, the National Security authorities decided to keep the members of the gangs in specific detention centres, meaning that there was a specific detention centre for the members of the MS13 (Mara Salvatrucha); another centre for the members of the La 18 – which are the two main gangs – and another [detention centre] for the remainder gangs, separating the “regular” population from the gangs’ members.

But this decision didn’t go with all the measures needed. There was also a strong prosecution of crime, during that time all the heads of the gangs were arrested and locked in. But the infrastructure was never improved, and, despite the increasing number of inmates, new staff was never hired and the staff that was already working weren’t trained to deal with the problem of having the heads of the gangs in those centres; people with very high purchasing power and a lot of influence and control in the country.

They practically gave away the prison system to the criminal structures. This means that they arrested them, they put them in prisons, they left them there and they forgot about them and they never made any effort to keep the prisons under control.

This is what is changing nowadays with this program to strengthen the prison system: the classification of the inmates by their degree of danger, and not by their membership to an “X” or “Z” structure; the creation of a new infrastructure suitable for each degree of danger; the compliance with our penitentiary law; the speeding up of the progressive regime so that low danger inmates, or those who are approaching the fulfilment of their sentence, are given appropriate treatment, and that they are not mixed with others that have another type of condition.

The control of the prison system is also attained through the improvement of the infrastructure, the modernisation of the action protocols, the placement of more technology, video surveillance systems and inputs’ control, the use of biometrics – for the control of inputs and identification of visitors – and 100% treatment of the inmates.

These are things that weren’t there 10 years ago and that we are currently promoting, a process that began in 2009 with the entry of our administration in the government.

We are practically in the final stage of the implementation of all this process, also by strengthening our correctional school with a new model of training.

Even if these extraordinary measures are being carried out, it is not true that prisoners spend 24 hours in their cells: hours for ambulatory freedom have been authorised, and there is also access to the purchase of goods and services through our system of institutional stores. There are restrictions in some centres; dosage and temporality are important and they are what enable these extraordinary measures to achieve the goal.

We have had a constant relationship with human rights organisations and with the Human Rights Attorney Office, which has unrestricted access to all our prisons. The right to health is not at any time even limited, in fact, we are providing health care with greater emphasis in centres that are under extraordinary measures.

Extraordinary measures are not measures to violate human rights, instead, they aim to recover and maintain control in these detention centres.

In a detention centre under measures (Ciudad Barrios), the inmates recently exploded a grenade, attacking each other within the same gang, the MS…

Weapons had been in their possession for many years, both due to the complexity of performing our inspection procedures and due to the overcrowding issue; also the accumulation of clothes and things that the prisoners take to the jail without major control… With the [extraordinary] measures we are able to streamline, deepen, and improve the inspection procedures.

There is a tendency for some leaders of criminal gang structures to order that some of their members do not eat their daily meals, so that they will fall into malnutrition and, possibly, the goal might be that they end up dead.

Then they take advantage of the situation to detract the application of the measures or affect our public safety policy. We are already taking the necessary measures to correct this situation, but that also gives you an idea of the seriousness of the problem we have with the gangs; they’re capable of anything to go on having control within the system.

JT: Are these extraordinary measures enough or do you plan further ones in order to control and hinder the power of the gangs?

RH: So far they have proved to be enough. The dismantling of the criminal structure and the isolation of its “heads” have allowed the daily average of homicides in the country to be reduced from 22 daily homicides – before the implementation of the extraordinary measures (95% of these homicides are linked to gangs, both as perpetrators or as victims) – to an average of 9.2 daily homicides, and the trend, from day to day, is going down.

The financial structure of the gangs has been razed and the territorial control that gangs used to have over communities has also been reduced.

All of this has to do directly with the control that is being taken in prisons, because there was a very direct connection with those who were in prison directing the criminal activity outside, in the streets.

JT: Would you please comment on the role that the external cooperation entities play in the reform of the Salvadoran penitentiary system?

RH: They are very important. We have a lot of international cooperation, especially from AECID, the Spanish cooperation agency. They have greatly supported us in relaunching our correctional school, in the training of our staff, especially with specific courses in penitentiary management and criminology.

The European Union has also given a great deal of support in the field of infrastructures: we have created a maternal and child sector, and an integral development centre for the female inmates’ children, which is a model-centre at the regional level. Much support has come from Taiwan – through construction and metal structures workshops – and also from the INL, of the United States, and from the Italian government.

All of these are the ones who have been collaborating with the penitentiary system in a sustainable and uninterrupted way since 2010.

JT: How do you see the future of the prison system of the country?

RH: Our vision is that the system becomes a modern one as far as technology, prison management and inmates’ treatment are concerned. We are moving towards a safe and rehabilitating model.

According to our figures, more than a third of our population will serve their sentence in the next seven years. That means that, if we are also able to speed up the progressive regime, we can contribute to the attainment of a less crowded system in which management can become more sustainable. If we fail to reduce the rate of overcrowding in the next few years, we are really going to have a very compromised system.

The training of the new staff is a great challenge: there has been a lot of corruption, but we must fight to change that culture through maintaining the control, improving training and providing greater opportunities to our staff in such a way that we are developing, for the first time, the penitentiary career through an organised system of promotions.

//

A lawyer and a notary, Rodil Hernández has also a degree in Business Administration and a master in Public Management, Justice and Security. In 2013, he was appointed Director General with the purpose of managing the penitentiary policy according to the principles that the law establishes, as well as the organisation, functioning and administrative control of the penitentiary institutions. He is a co-author of the Penitentiary Policy of El Salvador.