Interview

Anne Precythe

President of the Correctional Leaders Association & Director of the Missouri Department of Corrections, USA

Staff is one of the main topics on which Director Precythe has focused her leadership efforts. She and her team are committed to creating a safer workplace, improving employee satisfaction thus, automatically, enhancing the quality of work and outcomes.

To this end, the Missouri Department of Corrections is investing in training and valuing the workforce. With this, it will be more and more possible to retain people, interact and intervene better with offenders and truly transform the organizational culture.

In this interview, Director Precythe explains her entire vision, talks about recent achievements and challenges, and also gives us an insight into the Correctional Leaders Association, of which she is President.

JT: Missouri’s Department of Corrections Strategic Plan focuses on three major themes: Creating a safer work environment, developing the workforce, and reducing risk and recidivism.

Can you tell us more about your focus on staff development and safety and provide some examples of initiatives that address them?

AP: When I arrived in Missouri in January 2017, the Department needed a more clearly defined mission and vision. Staff needed to know how they fit into the organization’s goals when coming to work every day.

So, my administration has made staff a priority, working alongside them.

While we’re still operationally working on the offender population, we believe that if we’re going to reduce risk and recidivism, we need a team that treats each other well. Then, they’ll automatically work with offenders better.

Staff retention was a big issue, so we took an approach of cultural transformation. One of our first actions was to identify the types of tools our supervisors needed to be effective with the people around them. We now focus on a set of concepts to guide our operation: trust, respect, rapport, value, appreciate and listen. Those qualities are so vital, they’re now embedded in our DNA.

Our vision is to “improve lives for safer communities,” and we do it in three ways: We make the workplace safer, we make our workforce better, and we reduce risk and recidivism, or, in other words, we make sure people go back into their communities better than they were when they came to us.

Making the workplace safer is about taking our vision statement and tying it to valuing our employees.

Appreciation and recognition are absolutely essential. We have already instilled this principle in 2,100 of our supervisors by training them in communication skills, which include practicing difficult conversations and emphasizing the value premise – the idea that every job is important and every team member contributes to the big picture.

We focused on how to train, retain, and support our staff. Through what we call The Corrections Way, we’ve trained almost 10,000 people in skills that enable them to communicate better up and down and around the chain, and we have ambassadors in all of our institutions who do regular refresher training sessions.

We have hired supervisory specialists to support those staff who are promoted to supervisors, and that approach has worked tremendously well. We’ve also been very intentional in how we bring people into leadership roles, be it frontline supervisors or administration roles.

My deputy and I meet with mid-level and higher promotions to talk about where we’re headed as a department, how we’re going to get there, and how we want them to help us get there. If leaders don’t know where we’re headed, how can we expect them to get us there?

Finally, we’re working on paying attention to the needs of our staff and their families. The work we do is shift-based and very stressful. Our staff see things in the workplace that some people will never see in a lifetime.

Corrections impacts the whole family. We are working to identify resources to provide staff with the emotional and social supports needed for them to be healthy and able to come to work. For example, we’re exploring options with licensed clinical social workers who can help provide wrap-around services for our staff —including confidential behavioral health services that can also assist with any potential mental health or substance use issues.

We also have post-critical-incident seminars where we bring up to 30 staff together for three days to work with a trauma specialist, mental health staff, behavioral health staff, support staff, and our peer action care team members to address trauma they have experienced on or off the job.

The correctional workforce today wants to feel purposeful and feel like they’ve made a difference. We must create an environment where they have sound interactions among themselves and with the offender population while balancing the safety and security of the job at the same time.

We've trained almost 10,000 people in skills that enable them to communicate better up and down and around the chain.

What innovative ways to reduce recidivism are you implementing? What have been the results so far?

AP: Our staff development efforts are the first step toward reducing recidivism. Ultimately the interactions that they have with inmates are going to impact offender behavior.

Our recidivism rates have steadily gone down for the first year postrelease. In 2017, that rate was above 15%, whereas the latest data, from 2020, showed it was below 9%.

We’ve also been a part of the Justice Reinvestment Initiative aimed at reducing incarceration and reinvesting the savings into a better system.

The Improving Community Treatment Success (ICTS) program has been set up in the scope of that initiative. The program’s goal is to serve probationers and parolees with significant substance use disorders who require wrap-around support to succeed in treatment. It is a “pay-forperformance” model that is really improving community treatment success. Each provider team includes a probation and parole officer and different specialists, depending on the client’s needs, including substance use, behavioral health, peer support, employment, and housing.

We have also revamped our Community Supervision Centers (CSCs). CSCs are residential facilities that provide a short stay aiming to delay or avoid the incarceration of probationers and parolees who are at risk of revocation.

We have restructured all our CSCs and Transition Centers with more programming and life skills based on cognitive behavioral interventions.

And we are cooperating with outside partners to provide offenders with assistance and job opportunities.

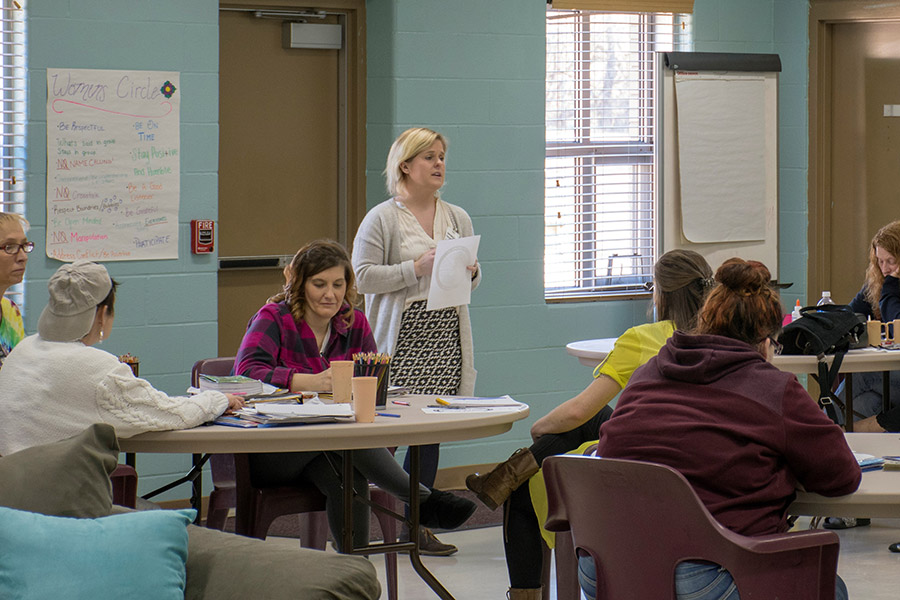

When I got here in 2017, Missouri had the fastest-growing incarceration rate for women in the U.S., and that was unacceptable. To tackle that issue, we designated one of our CSCs to specifically focus on women. And it has been a game changer for women offenders, as we are seeing that most women on supervision are not returning to prison.

We established re-entry centers inside some of our prisons, and we’re adding more as we go. Among other services, inmates can go to the reentry center, sign up for an appointment, and look for jobs online.

We are also very focused on education. The ability to provide higher education opportunities is vital for the incarcerated. They need hope for a better future when they come out, and nothing screams hope for the future more than education.

If higher education speaks to them, I want to be able to provide it. Right now, we have partnerships with nearly a dozen colleges and universities, and we’re continuing to expand the degree programs available.

We offer plenty of vocational education classes too, focusing on the required skills for today’s workforce; it’s not just the basic cosmetology and woodworking classes that it used to be. We have a partnership with a company out of Ohio that teaches roofing.

We offer programs in coding, welding, industrial wiring, and fiber optics, and we have heavy equipment operation and truck driving simulators. Partnerships with companies that come in and train offenders are crucial, as they will then hire people with past felony convictions.

This is another area where we have seen success. In a study supported by the Coleridge Initiative, we found that ex-offenders who received vocational training while incarcerated also had a higher-than-average rate of stable employment one year after release – about 7 percentage points higher than all released ex-offenders. This stabilization is important to reducing future recidivism.

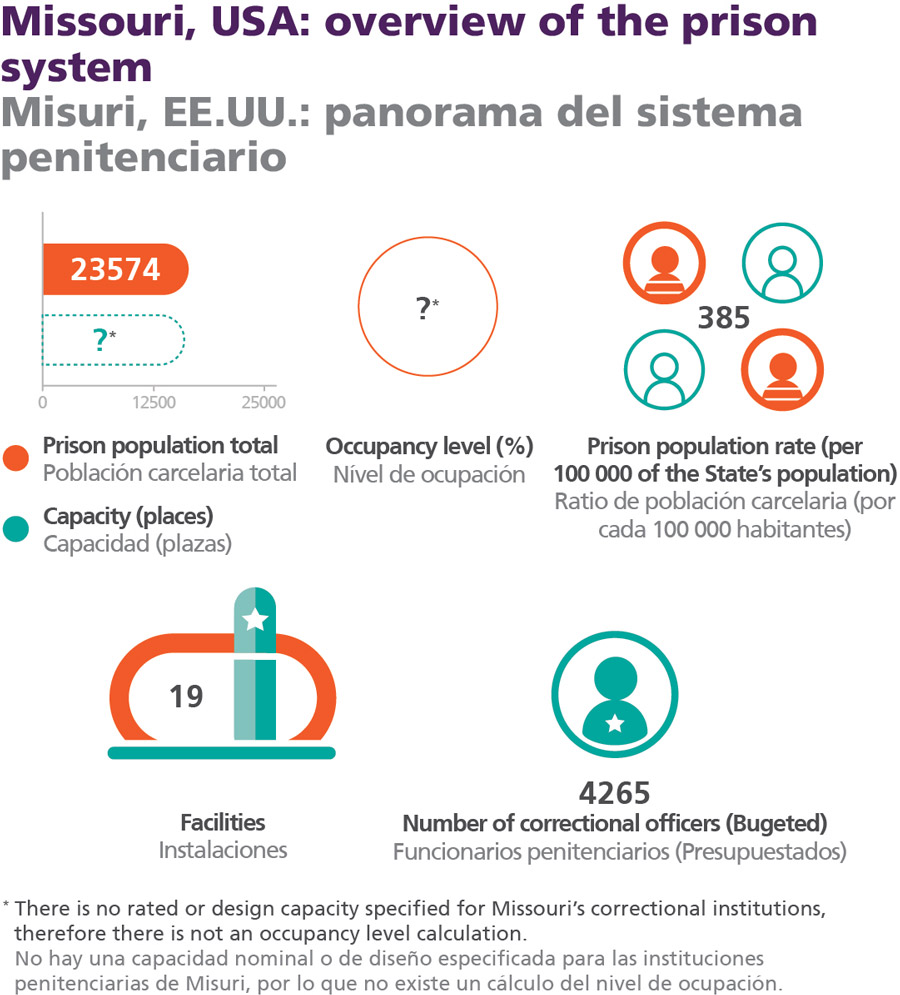

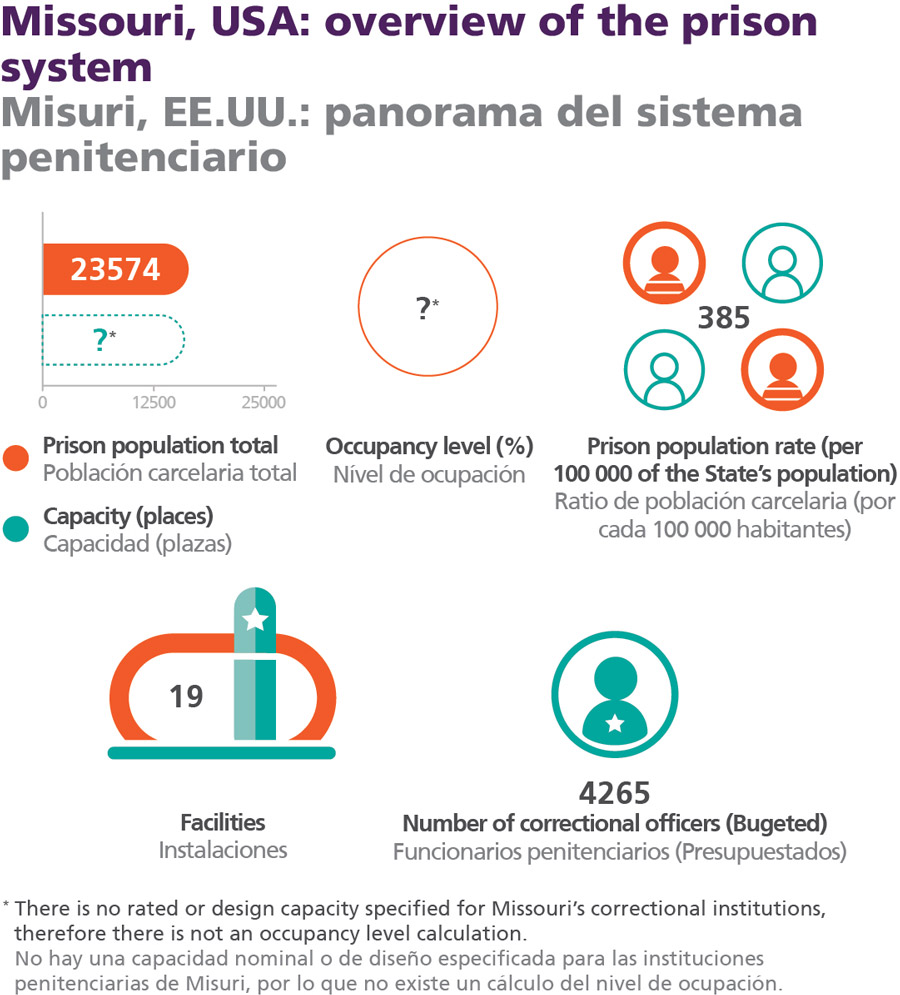

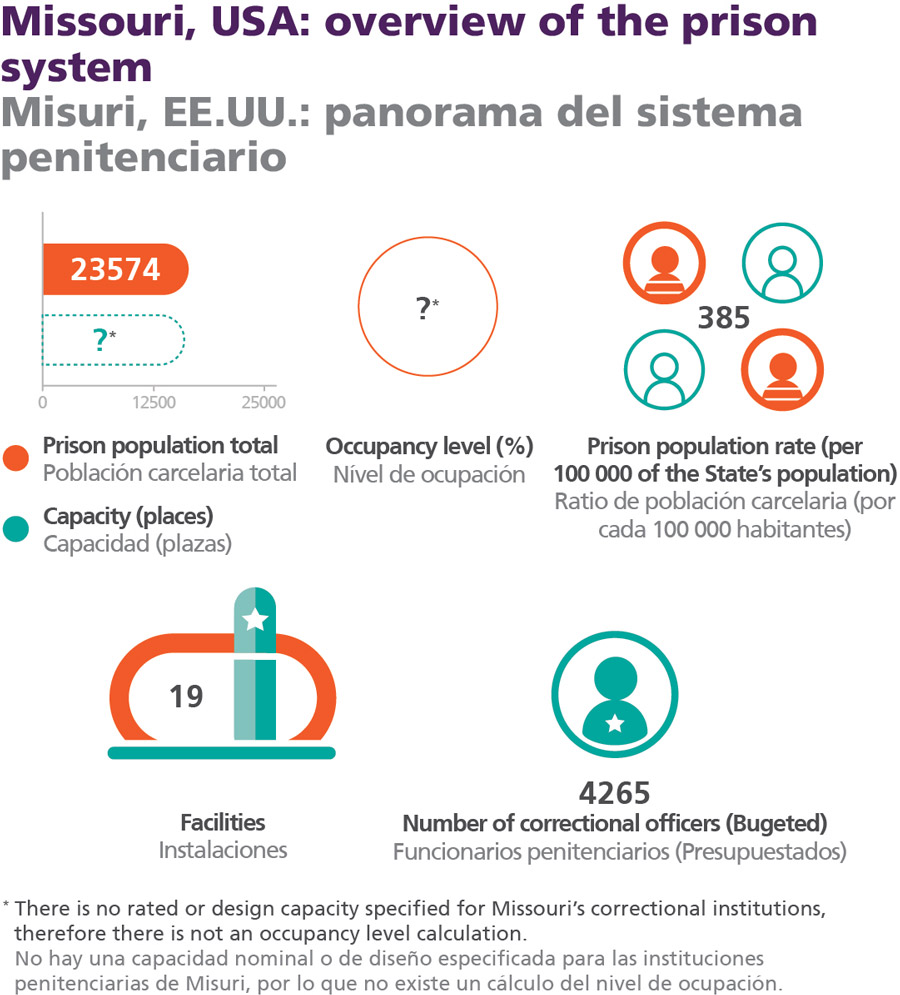

JT: The United States has the one of the largest prison populations in the world and a historically high per-capita incarceration rate. In the last years, a significant drop can be observed in the country’s incarceration rates (1). Missouri has seen a decrease of 30% in prison population from 2017 to 2021 (2).

How do you see this trend? And how does the Department contribute to promoting alternative community-based sentences, especially seeing that your career experience is considerably linked to community corrections?

AP: We have changed the way we do case management in Missouri, and I think that has contributed to some of the decline in the prison population.

We’re now focusing on following evidence-based practices and focusing attention on the high- and moderate-risk cases. We’re notifying the court of technical non-compliances and saving violation reports for the serious non-compliance and new laws violations. We have relied on the data that we review more and more to help guide our practices.

Our restructured CSCs are also diverting at-risk individuals from prison. Over the four years since the CSCs were repurposed, violations of the conditions of supervision within the first three months after exit dropped by more than 35%.

In fact, more than 70% of individuals who come to a CSC are at serious risk for revocation. Two years after exiting the CSC, only about half are (re)incarcerated. That’s about a 25% risk reduction, which is pretty significant.

Also, there was a major change to the criminal code in 2017, which contributed to a drop in the number of people sentenced to prison.

Our Department is not responsible for alternatives to prison sentencing, and we don’t do pretrial work, but we do believe in using graduated responses and cognitive tools to help restructure a client’s thinking while on supervision in the community.

What were the standout challenges and opportunities brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic? What kind of changes are there to stay post-crisis?

AP: Corrections was one of the few industries that did not stop. In fact, we ramped up and ran faster and harder, and we hardly got any credit for it.

Yet, I could not be prouder of every single person who works in Corrections for how we managed COVID; we had to figure out quarantine and isolation spaces, how to move the population differently, how to feed them differently, how to keep getting the work done, how to house them and do recreation differently. Everything had to be thought of in a different way.

We had great communication with staff and the offender population. We were already doing telehealth, but it ramped it up significantly. And we realized that we could do a lot more through video conference apps, so we utilized them more.

We stopped visitation for a period of time, and before we restarted we had every institution ask staff and offenders what safe visitation would look like. We opted for a scheduling approach, where people had to call and get on the schedule so we would have fewer people in the visiting room at one time.

We developed a viral containment strategy, which was based on eliminating cross-contamination among housing units, and we added it to our Emergency Plan. We had one of the most aggressive approaches to COVID testing in the country, which included doing wastewater testing from the beginning. We collected COVID data and followed what those data were telling us.

One year into the pandemic, the New York Times evaluated prison systems’ COVID rates, as compared to the rates in their surrounding communities, and ours was one of the lowest in the country.

Community corrections had to go remote, and we didn’t have laptops for everybody, nor did we have internet capability for some people in rural areas. Nonetheless, we were really creative. We even saw drive-through check-ins with probation and parole officers.

The other thing that probation and parole staff did a lot was video call visits. Probation/parole officers could see the clients in their environments, could see the parents at home with the children doing schoolwork and could get a better glimpse into the day-to-day lives of the clients. So, COVID did have some silver linings.

Corrections doesn’t run from crises, and our people certainly did not run from COVID-19. They stuck right in there, and I just could not be prouder of how they handled the challenges.

Today’s corrections professionals want to feel that they're making a positive impact. That's going to require us, as leaders, to really think differently about how we structure day-to-day activities and manage behavior inside our institutions.

What other challenges and achievements do you foresee for Missouri’s Department of Corrections?

AP: I think increasing our workforce is going to end up being a longterm challenge, and that provides us with an opportunity for us to think about how to do things differently in this business — how to make this not only a great place to work but also a place where everyone feels valued, included, and heard.

Today’s corrections professionals want to feel that they’re making a positive impact. That’s going to require us, as leaders, to really think differently about how we structure day-to-day activities and manage behavior inside our institutions.

And I really believe that we need staff involvement to help us figure that out. And the involvement of the offender population is also crucial because they need a voice in this transformation process, to be invested in doing differently themselves. Ultimately, we want our Department to be known as one of the best agencies to work for.

If we can do that, then our people will come to work, they’ll stay at work, and we’ll be able to get where we want to be in the long run.

There’s a lot of offender programming we continue to need. For example, we’re very interested in connecting offenders to jobs before they leave prison and helping prepare them for continued success in those jobs.

We can’t just get them a job; they also need community support and somewhere to lay their heads down at night. Housing is a real challenge. They also need health care, family support, emotional and peer support. Our mission is quite complex, but it’s a challenge I enjoy.

You are the President of the Correctional Leaders Association Board. What is the Correctional Leaders Association and what is it focused on?

AP: The Correctional Leaders Association (CLA) is an organization whose members are the CEOs of corrections in the United States. CLA members lead U.S. state corrections agencies as well as the corrections agencies of Los Angeles County, the District of Columbia, New York City, Philadelphia, the Federal Bureau of Prisons, military corrections, and any U.S. territory, possession, or commonwealth. Together they lead more than 400,000 correctional professionals and approximately 8 million inmates, probationers, and parolees.

CLA’s mission is to promote the profession of corrections, support each other, and influence policy and practices that affect public safety.

As president of CLA, I look forward to connecting the JUSTICE TRENDS Magazine with many of the innovative directors, commissioners, and secretaries across the United States for future highlights. We are interested in learning about corrections innovations that are working well in other countries, and we’re also eager to share the creative initiatives that work well for us. As I constantly say, we are a new generation of correctional leaders.

JUSTICE TRENDS can help us continue to learn from one another, and I look forward to connecting those dots!

References:

(1) Kang-Brown, J., Montagnet, C., & Heiss, J. (2021). People in Jail and Prison in 2020. Vera Institute of Justice.

(2) Kang-Brown, J., Montagnet, C., & Heiss, J. (2021). People in Jail and Prison in Spring 2021. Vera Institute of Justice.

Anne Precythe

President of the Correctional Leaders Association & Director of the Missouri Department of Corrections, USA

Anne Precythe began her career in corrections in 1988 as a probation and parole officer in the North Carolina Department of Public Safety, where she became director of the Division of Community Corrections in 2013. Precythe has been president of the national Correctional Leaders Association (CLA) since 2020. She has served on the National Institute of Corrections Advisory Board, the Council of State Governments Justice Center Advisory Board, and the Council on Criminal Justice. In 2021, she was named Civic Leader of the Year by the Greater Missouri Leadership Foundation.