Prison gangs are pervasive in American corrections. According to official figures, thousands of inmates are currently affiliated with gangs, with dozens of such groups in the United States. Although high, these numbers likely underestimate the influence of modern prison gangs. Apart from their official members, gangs also have a large network outside the prison walls, such as drug dealers, smugglers, and informants. Virtually unheard of until the 1960s, prison gangs are some of the country’s largest criminal organisations.

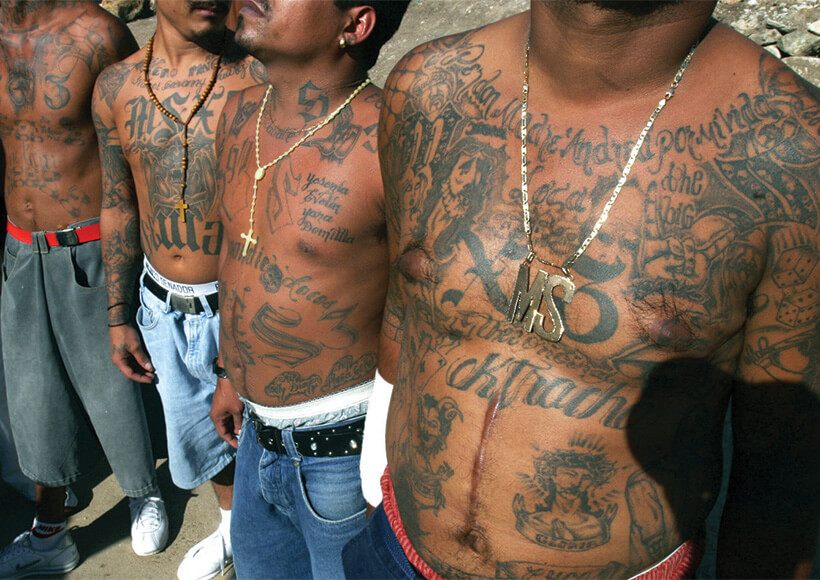

Gangs have a well-known history of violence. Their members are some of the unruliest inmates in their prisons, and prisoners are often recruited to gangs precisely because of their aggressiveness. Gangs account for a large share of cases of misconduct in the prison system and pose a serious threat to new inmates and correction staff. Prison gang clashes are frequently lethal not only in the United States but also in other countries such as Brazil, Mexico or El Salvador.

Yet, despite their tactics, gangs are not as unruly as they first seem. In a series of articles, David Skarbek notes that gangs have a cohesive structure, rigid organisational procedures and clear codes of conduct. Their main function is to provide governance: they operate as quasi-governments where the state is unable or unwilling to enforce contracts and maintain order.

Prison gangs also engage in trade, an important part of inmate social life. Given that inmates do not have access to goods, such as alcohol, cigarettes or staple foods, they usually acquire these via illegal trading. Prison gangs largely regulate those markets; gangs provide security for transactions to take place and solve eventual conflicts between trading parties. In this regard, gangs are not irrational. These organisations tackle problems similar to those of any other large group, that is, how to make individuals abide by contracts and contain violence between members of the group.

While society uses the legal code and the State apparatus to address these issues, gangs use the “community responsibility system” (CRS). CRS ensures that if an individual does not behave as expected, such as not paying their debts, the whole group is responsible for the fault. So, any person can be affected by the mistakes of another group member. In prisons, gangs play a similar role.

Gangs have information about the behaviour of their members and, as such, are able to monitor individuals and punish defectors. This increases the levels of social trust between parties, thus allowing trade to expand in prisons. It is cheaper for each group to punish misbehaving individuals than to lose the gains from trade, thus all parties have an incentive to maintain the system.

Another factor that caused the rise in prison gangs was the growth of the inmate population. Until the 1950s, prisoners largely abided by the “convict code”, a set of unwritten rules of socially accepted inmate behaviour. In the following decades, the vast inflow of prisoners unfamiliar with the code led to its progressive erosion. As the number of inmates grew larger, and previous norms weaker, the demand for personal protection increased. Gangs then stepped in to supply what prisoners needed: by using violence and concentrating power, gangs provide safety to their members when the convict code fails to do so.

In summary, prison gangs are a rational, albeit violent, response to the demands of incarceration. They promote cooperation within the prison system, via the “community responsibility system”, and enforce contracts and solve disputes, similarly to legal institutions. Prison overcrowding and the decline of the convict code have both increased the demand for private protection, and gangs are currently the prevalent mode of social organisation in jails.

//

Danilo Freire is a Postdoctoral Research Associate in the Political Theory Project at Brown University, Rhode Island, United States of America. His research interests are political violence, prison gangs and computational social science, with a special focus in Latin America. He holds a PhD in Political Economy from King’s College London and an MA in International Relations from the Graduate Institute Geneva, Switzerland.

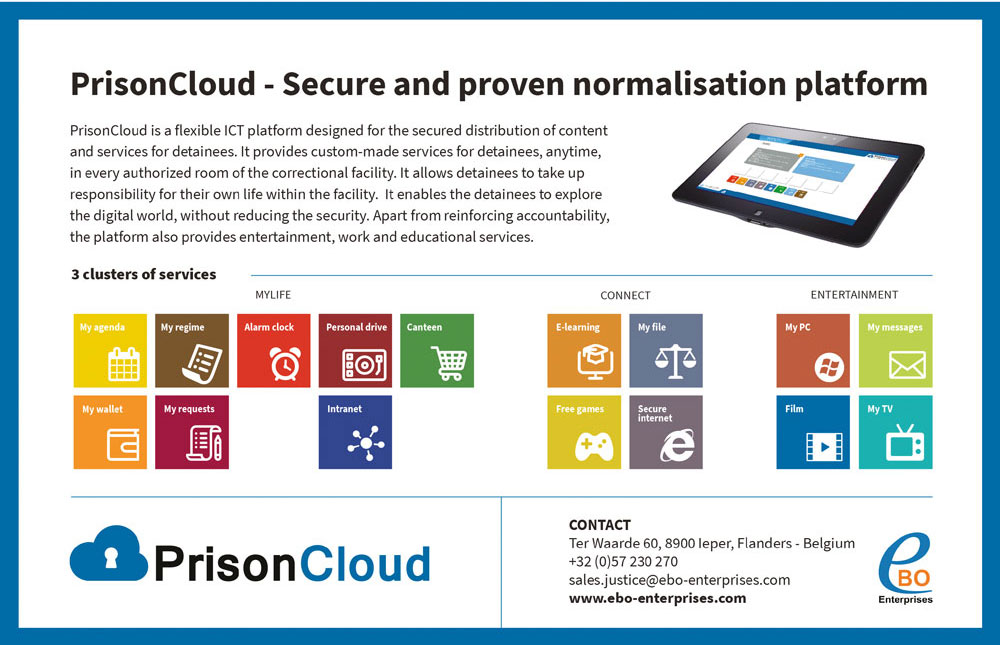

Advertisement